The Odd Couple: Up Around The Sun's Old-Time DIY Americana

The Odd Couple: Up Around The Sun’s Old-time DIY Americana

(Up Around The Sun at Lowe Mill Arts & Entertainment in Huntsville, AL, 2021.)

What do a relatively straight-laced information officer from the Department of Insurance for the state of Texas and a legendarily freewheeling Austin skate punk/funk/soul/garage rock icon have in common?

At first glance, it may seem like very little. Yet, take a closer look— and listen— and a deeper resemblance emerges based around a shared ethos and devotion to Do It Yourself sounds and folk idioms that transcend time, space and genre, while also maintaining relatively distinct spheres of influence and patronage. Blurring the lines between the staunch traditionalism of old-time porch music and the no rules attitude of post-modern art, Up Around The Sun— comprised of banjo player Jerry Hagins and guitarist Tim Kerr— aren’t just defying the laws of convention for the sake of it. Instead, through no other conceit other than just being themselves, the instrumental duo are revealing some of the various through lines in distinct strains of American music that might befuddle the average listener unfamiliar with the similarities inherent to their seemingly disparate, yet interconnected worlds.

You could call them an odd couple, but that might miss the point entirely.

Having both participated in DIY music-making in their own unique ways— with Kerr being at the cutting edge of the underground Austin music scene for almost fifty years through his time in bands like Big Boys, Poison 13, Bad Mutha Goose and the Brothers Grimm, Lord High Fixers and countless other ensembles; and Hagin deeply involved in old-time folk circles throughout his entire adult life— their diverse backgrounds are, in some ways, exactly what brought them together in the first place. Having first crossed paths at jam sessions at a local coffeeshop in Austin called Rio Rita’s back in 2013, after Kerr had taken up traditional Irish music on the side some years before, their innate camaraderie was born out of a mutual curiosity that eventually turned to admiration. Delving into the canon of old-time music together, Kerr, whose unorthodox approach to the songs he was learning utilized opening tunings in a setting that relied heavily on more standard string configurations, was a bit of a puzzling presence at first. Especially as a tattooed surfer-turned-skateboarder who was a member of the Texas Music Hall of Fame for his more raucous punk offerings he had been a part of over the preceding years. But that didn’t deter Hagins, who saw in his adventurous style a chance to stretch out not only his own musical chops playing traditional clawhammer banjo, but the form as a whole.

And thus the band was born. Fun, informal, and most importantly open-ended in their approach to their repertoire, Kerr and Hagins slowly became a working unit that has now released three proper albums, a live cassette, and a special split 7” of covers alongside Kerr’s longtime pal Mike Watt and his Secondmissingmen, that saw them covering the Minutemen’s legendary ode to the transformative power of punk, “History Lesson (Part II),” in an inverted folk style that both flipped the song on its head while also honoring its original intention and spirit. Which is no mean feat. Having added a chorus of legendary figures from across the punk spectrum— including Tim’s wife Beth, John Doe from X, Mark Arm from Mudhoney, Cait O’Riordan from the Pogues, Ian MacKaye from Minor Threat/Fugazi fame, Alabama rocker Lee Bains III, among many, many others— with each person taking turns singing lines from the song, it stands as an incredible tribute to not just Kerr’s musical roots, but his newfound love for a different kind of DIY crowd with a very similar operational aesthetic built primarily around a shared sense of community. And as it turns out, it wasn’t that great of a stylistic leap for him after all. Having grown up as a teenager in Texas listening to people like Richie Havens and English folk-rockers Pentangle, Kerr’s interest in acoustic music preceded his immersion into punk by several years, making him a natural fit for a scene that welcomed him, and his unique approach to their music, with open arms.

Having recently put out a new album titled Water Valley— produced by Matt Patton from the Drive-By Truckers and Dexateens, and released on his Dial Back Sound imprint based out of Water Valley, Mississippi— Up Around The Sun are hopefully positioned to finally reach a (somewhat) wider audience outside of the confines of their native Texas and the more insular old-time music scene. Having largely played house shows and small venues around the country over the years, they are now set to embark on their second tour of Japan this coming week, where they will reconnect with old friends and musical companions, like renowned Japanese folk musician Bosco, and continue their mission to bring old-time tunes to as many people as will listen, and maybe help influence a few others to pick it up along the way.

It’s all part of a greater musical journey both have been involved in since they first picked up their respective instruments many decades ago, and is something of a crusade now, making them ambassadors for an archaic art form that is constantly in search of new life. Which is exactly what they provide.

To learn more about them, their music, and their fantastic new album, I sat down with Tim and Jerry to see just what kind of personal intersections they were discovering on their own, and how any of this ever came together in the first place.

This is what they had to say.

AV: I just want to ask you to start off with about the genesis of the band in Austin and what brought you all together as a group. Did y'all know each other personally before playing together?

TK: Well, I mean, we've known each other before playing in this, but we didn't know each other.

JH: We knew each other socially, just jamming, playing old-time music. So we got to know each other through music. And the funny thing is I didn't know about Tim's music. I didn't know about his music history, which is extensive. I’d never heard of it. I was a folky. So we started just jamming old time tunes, and then as we got to become friends, then we started playing together as a duo and it led to what we're doing now.

TK: Yeah. There was a club here that's called Beerland, or was called Beerland, now it's The 13th Floor. Beer Land sounds like a Simpsons episode, but Randall’s really great, the guy that ran it and stuff. And he started a new thing up called Rio Rita's on East 6th, and he missed seeing me and Beth, cause Beth and I weren't really going out now, ‘cause I was playing Irish music on button accordion and stuff. I was going to people's houses and playing and I wasn't really going out to clubs that much anymore. So he missed us and he wanted to start a session. So we started up a session. It started out at first it was Irish and old time, but there's a whole lot more people playing old time than there is Irish. And I would pick up the guitar first and play like you're hearing this stuff [Up Around the Sun music], but then when other guitar players would show up, they were just like, what the hell's going on? ‘Cause I'm not playing anything at all like what you're supposed to be playing for this stuff. And I'm in an open tuning. So then I just got Jerry to come over and start showing me how to play clawhammer, you know, ‘cause I wanted to just start playing banjo and skip the guitar. And then at some point, I think it was right around then that you asked me to make a tape of us playing together like we used to, like Rita Ria’s was sounding.

So, anyway, that's how this kind of started. And then there's a little film that kind of tells the story. It's pretty great. But, basically what happened was, made the tape and gave one to Jerry and the guy from Monofunus [Press, record label]. Which is actually the very first record [2013’s self-titled LP]. Some people keep saying this is the third record, but actually it's the fourth record. And the very first one was on Monofunus and it happened because he had reissued an art book that I'd done for Altamont, that skate company. And he had brought some over for me the day after we made this recording on the computer or whatever. And he asked me what was going on, and I said, “Oh, well, Jerry was here,” and gave him a recording of it. And then he literally called that afternoon. It was like, “Do you want to put this out?” It was just like— cause we didn't have, there wasn't any kind of band in the air, like there wasn't a name. There wasn't anything. So we didn't have a name for a while.

AV: And where did the name come from? Was there an inspiration for it?

TK: I think it started out being Way Up Yonder Above The Sun or something. I can't remember why, but then it just turned into Up Around The Sun. So I don't know why I came up with that.

JH: I think it's a cool name as band names go, you know? What does any band name really mean? We don't know, but we like it.

AV: Yeah, it's great. So how long have y'all been performing together now?

JH: I’d say about 15 years.

TK: It’s been a long time.

JH: That record [self-titled debut] came out in 2013, which is 12 years ago. Maybe 13 or 14 years.

(Cover art to the first, self-titled Up Around The Sun LP, 2013.)

TK: It’s been a pretty good while, 'cause we don't really ever play that much, because the music is so quiet that it really doesn't go over that great in clubs because everybody's in there talking. And then at the same time we don't have a singer, so there's not somebody to focus on. So we just kind of turn into this background music. And it's not a vain sort of thing where it's like, “Oh, it's my music, listen to what we're playing.” It's more that I’m playing off of what Jerry's doing. And I think he's playing off of me. I know he is because I hear him do certain things that are different sometimes— the stuff's pretty great. So when I'm listening to him and somebody starts talking, I kind of start hearing what they're saying and I get distracted because it's like, “Oh, Sally did what?,” kind of thing. So, it's so much easier to play places where people are there to hear what's going on, you know?

JH: Yeah. So I guess we'll play like art galleries or record stores.

TK: Or house shows— we’ve done some of those and stuff.

JH: We’ve played in a Kabuki theater.

TK: Yeah, that was good. We're going to do that again this year, which is great. That place was cool.

AV: Is there a coffee shop scene— like a folky coffee shop scene— in Austin?

TK: I don't know if there is.

JH: There is, but we don't beat the doors very hard on it. But yeah, we've played some coffee shops.

TK: But once again, even like coffee shops a lot of times, everybody's sitting there to visit and talk and stuff. You know, nothing wrong with that, but I'm just saying for this kind of stuff, it's just hard.

JH: And the expresso machine makes all that noise. [laughs]

AV: Is there a big folk scene in Austin? Is it more of a smaller community?

JH: There is. There’s a lot of music here, of course.

TK: Jerry plays a lot of old-time and bluegrass. A little bit of bluegrass.

JH: A little bit.

TK: He's more in tune with all of this. I'm like Sun Ra: not of that world or not of that orbit. But I like it.

AV: Carpetbagger.

JH: There's a pretty good old time [scene]. Are you familiar with the difference between old-time and bluegrass?

AV: I am! Yeah, absolutely.

JH: Okay. ‘Cause a lot of people aren't, as you know. So there's a pretty big bluegrass scene and there's a lot of the younger bluegrass players showing up. And then for the old-time, there's also a lot of younger people being drawn to that. Then there's singer-songwriter kind of folk. But yeah, Austin's a pretty good town for traditional music. More so than Houston or Dallas.

AV: I could see that.

TK: Really?

JH: Oh, yeah. By far.

(Short mini-documentary on Up Around The Sun, 2018.)

AV: Well, I’m curious, Jerry, once you did find out about Tim's other music, what did you make of it? Have you listened to all of that— Poison 13, Big Boys?

JH: I love everything I've heard. And back in the days when Tim was playing that music, I was listening to some rock, punk, new wave.

TK: Well, it was back when all that first started. There wasn't punk, new wave— it was all the same thing. They just didn't know what to call all these “weirdos doing what they can't figure out what this is, kind of thing.” And Jerry listened back then, because he'll tell me about listening to Jonathan Richman or things like that. He'll tell me about the kind of stuff that he listened to, but yeah, he didn't listen to hardcore. That definitely didn’t happen.

JH: Mainly I would buy records like Jonathan Richman or Camper Van Beethoven or Talking Heads, things like that. But I wouldn't go to shows. When I went out, I went out to play music with friends with the fiddle. So, I didn't dive that deep into it. And I wished I had. But I came to it late.

AV: Are you from Austin originally?

JH: Not originally. I moved here in the early-90s. I'm a Texan, but I did live in Philadelphia for a long time.

TK: We actually realized that he went to the same high school that Mike— that was in Poison 13 and Lord High Fixers and all that— they were in the same high school. But Mike didn't know it. But it must have been like probably when he was a senior— Jerry— Mike was probably still in junior high. And then the next year when Jerry's out, was when Mike came in. I think he was probably a freshman at that same school. We just found that one out fairly recently, which I was just like, “Oh my god, that's pretty great.”

AV: Little synchronicities there. That's funny. Well, I'm curious about your delving into more traditional music away from the punk scene. When did that really start for you? Is that something you'd always had an interest in?

TK: Yeah, ‘cause junior high and on I was already listening to a lot of John Martyn and Nick Drake, and Bert Jansch and Pentangle, and all that kind of stuff. And I kind of seemed to go in that direction as opposed to going into Deep Purple and Black Sabbath and all that. Which was fine, but it’s just, something about that music, and kind of what we're doing now— the way those chords happen— just really resonated with me inside. So I really always gravitated towards that. So pretty much doing that all the way. I mean, when Big Boys started, it wasn't the music that made me want to do that stuff. It was the whole community of it that I just thought was the most amazing thing ever. That everybody in this crowd is doing stuff. The crowd is just as important as the band is. All of that was just like, “Oh my god, this is fucking great. Like, what the hell?” And so, we literally did flip a coin to see who was going to— ‘cause I was playing all these crazy tunings, like David Crosby tunings and all this stuff, and actually played at Kerrville [Folk Festival]. I played there once for a songwriter thing, and then I was supposed to go the next year, but I broke an arm at a 14-foot pool in Bastrop like right before, so I didn't go play that. And literally when we started and flipped the coin, you know, Chris [Gates, bass player] played kind of more like what Junkyard ended up playing. He was kind of playing Ted Nugent and that kind of stuff. And at that point I was so locked in to all the acoustic stuff, and also soul and old, old funk. And I got guitar and he got bass. And if it would have been the other way around, it would have been a completely different sounding band.

Plus, the reason I play like I play, when you see me playing like a standard tuned guitar, I'm so used to things kind of ringing out and being more open, that I open all the chords to begin with, if that makes sense. So like, a good story for that is like with Monkeywrench. I would send them stuff and then they'd have to literally wait for me to get up there, and then they'd be like, “Oh, what? Oh, it's an A chord! It's an A chord he's playing!,” kind of thing. [laughs] Because the way I do things, and the way it sounds isn’t— I don't know— I think I said it in that film, like, for some reason, I don't do anything the way you're supposed to be doing it. [laughs]

AV: Yeah…. [laughs]

TK: You know, it's not on purpose. I just play it different.

AV: That's funny. I've seen the film you mentioned and you say it's taken a little bit of adjusting with other people from the old time scene with having that style sort of interspersed with what they're doing and more traditional tuning.

TK: Yeah, I think for the most part a lot of people like it, but it's absolutely not that traditional at all. I mean, when we first played with Bosco [aka- Takaki Kosuke, old-time musician from Japan], I didn't know who Bosco was. And then when he [Jerry] found out we were playing with Bosco, he was like [makes a shocked expression]. You know, ‘cause I just was doing DIY, old school, what we all came from kind of thing, and it's just like, “Oh, somebody in Kyoto plays old-time. Hey, you want to come up here and play with us?” You know, kind of just that kind of deal and he sat down right at sound check and they were setting up stuff. That's the beauty of this stuff too, is we could literally do it right here while you're looking at us, you know? It's like, you don't have to have all that stuff. So we're playing on the floor. And when it was over, he said to me, he goes, “You know, I listened and I really liked it, but I just thought, I'm not going to be able to play to this.” ‘Cause for some reason, what I'm doing, a lot of the tunes aren't even the tunes anymore to people that are really steeped in it. Like they won't recognize what we're playing or what's going on. But he said, as soon as we started, it was like, “Oh yeah.” So now we're really looking forward to going back up there and playing with him.

AV: That’s awesome.

TK: He’s kind of like a Spot character, which is really great.

(Tim Kerr, Bosco and Jerry Hagins.)

AV: Well, I was curious, in talking about the punk scene, do you see any parallels or similarities between the DIY spirit of old-time music and folk music? I mean, that's really where that comes from. And Jerry, I was going to ask you from your perspective, and then also from your perspective, Tim.

TK: Well, one of the first times I got him to come over and start showing me— ‘cause I wanted to make sure I wouldn't fall into a habit I wouldn't be able to get out of for doing old clawhammer— and he came over, and of course I don't do that like normal people do it, but he said I was fine and it looked really great and all that kind of stuff. And then at some point while we were playing, he was just talking to me. He was telling me about Clifftop [aka- Appalachian String Band Music Festival] and things like that, and he was telling me that, you know, “I think old time has a lot more to do with punk rock than it does bluegrass.” And I said, “Yep.” Because of the community of it and stuff.

JH: It's kind of a joke, but they say in bluegrass, “everybody knows the song before they start.” In old-time, they know it when it's over. So you learn the tune by playing it with people and listening. And only half of it is really musical expertise. I think the other half is all social. Just talking.

TK: It's a musical conversation.

JH: So, I think there's a lot of similarities to it. And when you said you got into punk not really for the music, but for the community, in old-time, no one expects to make money playing old time music. Bluegrass, you can. But for the old-time you play it because you just like the tunes and you like the people. There’s probably half a dozen people in the country that make money from old-time music. Most just do it for the love of it.

TK: I mean, the other thing that's funny too, is that at some point early on, when we were talking about that, was that we kind of came to the conclusion that old time is to punk rock, what bluegrass is to heavy metal. You know, because heavy metal is all showing off, and it's a whole different attitude.

AV: Who can do the fastest runs.

TK: Yeah.

AV: That's really funny. Well, it's interesting because I think of old-time as sort of like campfire music, or front porch music, and it's for sitting around, whether you're having a little bit of tea or maybe you're having a nip of whiskey or something, passing that around.

JH: Definitely front porch music for sure.

TK: You know, speaking of that— this is probably on the subject, off the subject— but your saying sipping tea or whiskey or stuff. At one of the times at Rio Rita’s, they went into this song that's called “Greasy Coat.” And then somebody starts singing it, right? While we're playing and stuff. And the words to it were, “I don't drink and I don't smoke, and I don't wear no greasy coat.” And I thought, “Oh my god! This is like the first straight edge song. Holy shit!” [laughs]

AV: It's like Minor Threat or something. [laughs]

JH: Yeah. [laughs]

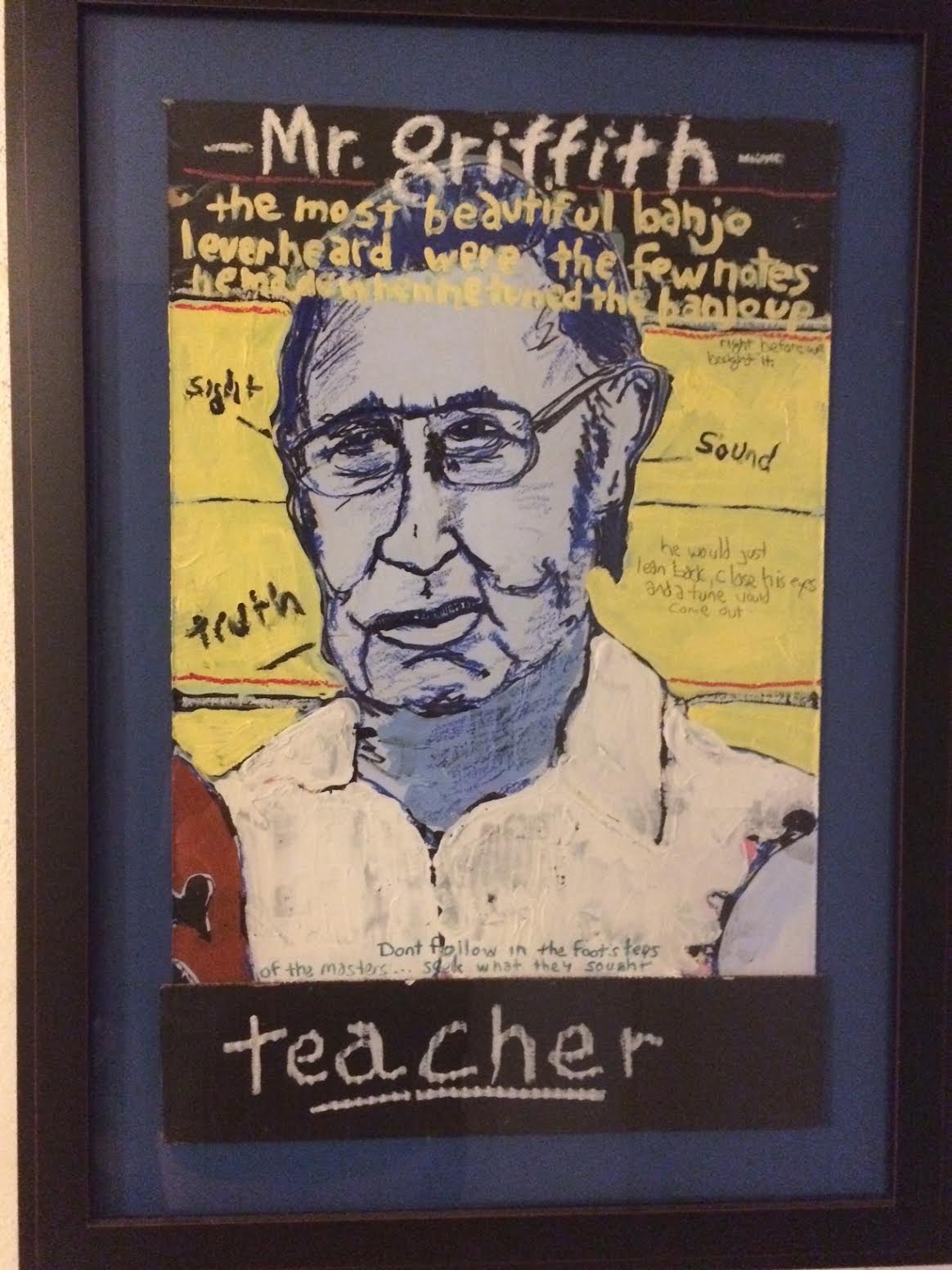

AV: I was gonna ask you, Jerry, about some of your influences, and you mentioned this and talk about it in the film, of Mr. Griffith, who I believe was your mentor. Who was he and what was his influence on your life and playing this kind of music?

JH: I really appreciate you asking me about Mr. Griffith. His name was Oral Griffith and he ran a music store in Arlington, Texas. And I— for my 17th birthday— my mom got me a banjo, and we bought it at that music store. And he was an older guy, and he wasn't really a banjo player, but he was a musician. So I would go once a week and he would just teach me old songs. And it definitely opened me up to the world of making music. I'd heard music on the radio and on a record, but the idea of making it was really novel to me. And he turned me on to that. He wasn't a performer. He just ran a music store. But my respect for him was so great that I've called him Mr. Griffith the whole time, and I still do. And you did too, so I appreciate that. No, he was just a guy, an older guy, who was kind of my guide into this whole world.

TK: Sensei.

JH: Sensei, yeah. So when Tim was interested in learning clawhammer banjo, he exchanged lessons for a painting and he did a portrait of Mr. Griffith from a photograph.

(Tim Kerr portrait of Oral Griffith.)

TK: Actually what he did was, ‘cause I said, “Well, I'll trade you a painting.” ‘Cause he was like, “you already got it,” as far as the clawhammer stuff. Even though, like I say, I don't do it like you’re supposed to. And I said, “Well, I'll tell you, I'll trade you a painting if we can just start playing the tunes we’re playing, so I'll kind of be up on it a lot quicker and stuff. And at that point in time, I didn't really have a banjo, and he was like, “Oh, well, that's not fair. I'm going to make you a banjo.” So he made this banjo that's really fucking great that I've got. And for the longest time, he was constantly like, “you really need to get a better banjo.” And I was just like, “You made this. This is great. This is amazing.”

AV: That's awesome. So coming full circle with Mr. Griffith. You're passing along some of that to Tim.

TK: He teaches now and stuff. We're pretty much the same age. I think you're just maybe months behind me or something. I don't know what. So we kind of came up in the same era, it's just we kind of went different routes. Although we kind of didn't, because I was playing lots of folk stuff before the punk stuff happened, so you just kind of stayed in that.

JH: Yeah.

AV: You had the circuitous route back to yourself?

JH: Yeah…[laughs]

AV: Speaking of influences and things kind of coming full circle, I know you were a huge influence, Tim, on Matt Patton, who recorded the new album in Water Valley. And his band Dexateens were one of the great…

TK: Yeah, they were great. That's one of the top three records to me that I've ever gotten to do is the Dexateens stuff, that very first Mooney-Suzuki record, and the Fatal Flying Guillotines. But all three of those were just like— I super love all the people that I got to do stuff with, and super honored and all that, but those are the three that really stand out to me. And the Dexateens stuff is freaking great.

JH: Who else was in that band that I've met? Was Pudd in there?

TK: No, Pudd was in Quadrajets.

JH: Oh, okay.

TK: I mean, the story of the Dexateens is so crazy. And I saw where he [Matt Patton] just recently, there was something he just sent to me day before yesterday or something where he was talking about the Dexateens stuff. I guess it's the 20th anniversary of that first record or something. Literally what happened was Dog [aka- Sweet Dog] like brought me up there. Because I guess Dog had come and seen Lord High Fixers at South By [Southwest]. We were playing some party or something. And this is back when I had the dreads. So they decided they were going to bring me up, or he did. I don't think any of the rest of them knew who the hell I was or whatever. And on a side note, they kept looking for pot for me, because they thought because I had dreads, I smoked pot. Which I've never ever smoked pot, ever. I've never smoked anything, you know, so it's just pretty funny. But when I got up there, most of the stuff they were playing was just— it was the Quadrajets, you know? It was just kind of like, well, why? Like we're just going to do Quadrajets Number 3 kind of deal. And then they played “Cardboard Hearts.” And when they played that, I was like, “Oh my god, that's fricking great!” And I remember Elliott looking at me going, “You like that?” And I was just like, “Yeah, that's really, really great. Do you have more stuff like that?” ‘Cause that's cool. That doesn't sound like Quadrajets. You know, the next version of them or whatever kind of thing. And so they ended up, I went back home, and then when I came back to Tuscaloosa, they wrote a bunch more stuff that was kind of more in the vein of that and stuff. But they're great. They're a really, really great band.

(The Dexateens’ “Cardboard Heart.”)

AV: It's funny now that you're flipping the script and here's Matt producing you down in Water Valley. Did that just come about naturally and that y'all talked about doing it? Or how did the new record come about and working with Matt?

TK: I think he asked. It’s kind of amazing to me, but at the same time I'm super honored. ‘Cause I'm just being me, you're just being a human being, you know? So it really amazed me when he was telling me all this stuff and he really wanted us to come up there and record. And I can't remember what was going on that we were kind of going to be— I think you had just retired, maybe— and we were going to start trying to figure out about maybe trying to do some trips. Because I really want people to hear this stuff and see it. ‘Cause I know that if it could get out to a broader group of people, I know there's a bunch of people that would really like this stuff, but don't have a clue what we're doing because they either think it's punk or I don't know what.

But I think that's what happened was I told him, “well, we're coming through here so we could stop.” And we ended up going for a week, I think, which was crazy for us. Because we usually record everything, like the thing with Bosco— I don't know what the hell was going on— but they decided that they wanted me to come and record, and obviously Jerry too, for free in Osaka. And I don't know if it was because of the stuff I've recorded, but they wanted to see how I did it. I don't know what. But so we brought Bosco, and when we walk in there like— and everybody that's recorded with me, or if you've heard stories, knows that I do it without headphones— and of course they had everything kind of like, here's one thing over here, one over here. So I put all the chairs together and just started putting microphones around us kind of thing or getting the guy to do that. And you can see the guy kind of scratching his head, like wondering what's going on. And from 6 to 10, we were supposed to record. And then Tuesday from 6 to 10, we were supposed to mix. We did 22 tunes from 6 to 10 that first night, which was pretty fricking great. I mean, just going, it was so much fun. I think we repeated maybe one or two of them. I can't remember what.

JH: And that’s kind of the nature of traditional music, is there's a lot of tunes that people share. Like everyone knows “Cripple Creek” or “Soldier’s Joy.” So you can sit down with someone you just met and you can play the same tune if you're listening, if you have your ears on. And so Bosco definitely had his ears on.

TK: Yeah, because he knows all that stuff.

JH: So yeah, maybe two takes. A lot of them were single takes on that record.

AV: Wow, nice.

JH: Now, in Water Valley, we worked on a setlist.

TK: We were there for a frickin week. Plus his Beth [Chrisman] was there who plays fiddle. She's really great. She's a singer-songwriter and we got her to come and help out and stuff. But yeah, like a week. It was great. I mean, I love Matt and it was fun being there and stuff, but a week is kind of a pretty long time for us. We could probably get everything done in three days.

JH: Yeah, we did a Dexateens song [“Devoted to Lonesome” from Red Dust Rising].

TK: I’ve always really loved— it's not necessarily my favorite song, although it's probably one of my favorites— but I just really, really love that line in there that says, “we've got history lying everywhere.” That's a frickin’ great line.

AV: For sure.

JH: And Matt played on a couple of tunes, too. That was fun.

AV: And were you aware of the history at Water Valley? Did you know about the history of that studio?

TK: Oh yeah, I totally knew all about that. And the first thing I did was sat in the chair that said T-Model. It was like, it was written on the thing, so I sat in that chair. And it literally, it was like a folding chair and a part of it was broke. So you're already in that position that he's always in [hunched over], and so I'm sitting there playing that, and after the first tune they stopped and told me I needed to get another chair because that chair squeaked. [laughs] I couldn't sit in that one. He played— it’s a crazy long story— but Sweet Dog brought them over to the house one time, T-Model and his band, right before they were supposed to play at Beerland. And we brought him into the front room. ‘Cause I remember saying to Beth [Kerr, Tim’s wife], ‘cause you know our house has been like a youth hostel since ’78 with all the bands and all these people and stuff, and I remember telling Beth like, “Okay, this is probably gonna be one of the weirdest things that's ever happened at this house. But, this is gonna be one of the coolest.” And we brought him in and they literally sat down in the front room. They didn't go anywhere else, they just sat down since they came in, and T-Model saw this guitar sitting by the couch that was just like a thrift store, $200 buck hollow body. And here we go, and started playing. And he's playing everything to my Beth, because she's a woman. And here he is just like going at her and singing all this stuff, and telling these stories that were the most cliché blues [stories]. But at the same time, it's like, no, he really did kill somebody. And it’s like, this is true. [laughs] And then when they got up to leave, he was saying to Dog, he's like, “Dog, I need a guitar. I can't hear my guitar. I need a guitar like this.” So I just gave him that one. I said, “You know what? Take that.” Like, for all the stuff you've ever done, here. Thank you. You know, that kind of thing. But yeah, I definitely knew the history of the place. I never had seen, but I definitely knew the history of it. And Beth and I actually stayed there. And they [Jerry and Beth] stayed at Bronson’s.

JH: Bronson, yeah. Right.

(Up Around The Sun’s cover of The Dexateens’ “Devoted to Lonesome.”)

AV: Speaking of covers. Besides the Dexateens cover, there's other songs you all cover on the album. What was the process of picking those tunes? Were they just tunes you play around the house and then when you all get together?

TK: Yeah, that's literally what happens.

JH: In the traditional music world, they’re sort of covers, but we don't really call them covers. They're kind of public domain tunes.

AV: It's oral history, essentially.

JH: Yeah. So there are certain musicians who have recorded, you know, “Ducks on the Mill Pond.” And when I play banjo on that tune, I'm thinking of that guy. So it's sort of a cover, but it's also sort of just the way that folk music goes.

AV: Right. It's sort of just handed around.It’s part of the beauty of it.

TK: And he knows so many of them. Unless stuff like this is happening— where we're going to Japan, so let's get together once a week so we can figure out what the hell we're going to do when we get over there and stuff— usually we get together every couple of weeks. He'll come over and I'll be like, “What have you been playing now?” And he'll play me a bunch of new stuff that he's been playing. And I'll play with him. And if things click right off, it's like, oh yeah, put that one down. Let's do that. That's pretty great. And some of them we kind of work on.

JH: There's one person, Tim's grandfather, Duck Wooten.

TK: Not my grandfather, Tim. Oh yeah, Duck Wooten.

JH: Yeah, different Tim. [laughs] There's a guy in town that’s a friend of ours, Tim Wooten. And he's a fiddler, and he plays a lot of tunes from his grandfather, who was recorded at home and on a reel-to-reel recorder in the late-50s.

AV: Oh wow.

JH: So, I always loved those tunes.

TK: So we play those. And Bosco knows them.

JH: And Bosco knows them. It's definitely local here to Central Texas.

TK: You know, and speaking of my dad, like you're saying grandfather and stuff. Both my brothers were 8 and 10 years older and they were both coaches at some point. So when here comes this kid that's into art, music and stuff, my parents, especially my dad, I think was really pretty happy that here came somebody that was not prom king and all that bullshit stuff. So he was always— really both of them— were really supportive. But he was really supportive with music and all that. So anyway, the last couple of years before he died I would come home and I would have the accordion or the banjo or whatever. So one time I came home and he was like, “What have you been playing?” And I said, “Well, I've just learned this tune called ‘Breaking Up Christmas.’” And I started telling him about the tune that I'd heard at Rio Rita’s when they were talking about stuff. And he's like, “Oh, I know!,” kind of thing. And I look at him, and he goes, “Oh yeah, we used to do that when I was a kid.” And I was like, “What kind of thing?” And he starts telling me all about going to the houses and them clearing out [to play and dance]. And I was just like, “Oh my god, I've never heard this before.” It was pretty great because I was saying to him, “Like fiddles and stuff?” He said, “Oh yeah.” I was like, this is pretty amazing.

JH: It is full circle.

AV: Very cool. Well, ya’ll also did a really cool split 7” with Mike Watt and the Secondmissingmen, where they covered Big Boys’ “We Got Soul” in this kind of soul jazz version, you know, which is really cool.

TK: It's like the DJ Screw version. Kind of slow.

AV: Yeah, I love it. The organ on it's great.

TK: It’s great, but it's just funny. I've been friends with Watt forever, so he was really intent on us doing something. And I was just like, well, first of all, we don't sing. And second of all, it's like, you know, Jerry kind of really needs to have some sort of a melody to be going off of when he's doing stuff. So at first I kind of thought about “Joe McCarthy's Ghost,” but Jack O’ Fire did that, the other band I was in. And we did a pretty frickin’ amazing version of that, and Watt really loved it and stuff. And then I thought about “History Lesson (Part II)” And I just thought, dude, nobody can do that song. That's Minutemen, you can't do that song. And then I realized that, I always thought D. wrote it, but then I realized Watt had written it. So now it makes sense when he says “I was John Doe.” So then all of a sudden a lightbulb went off, and I realized, you know what? And I just sent out emails to all kinds of people. And it didn't have to be somebody that was famous. It was just anybody that I knew had come from that period and had met. Like This Bike Is a Pipe Bomb. Terry's [Johnson], saying the thing of, “this is Bob Dylan to me,” kind of deal. I made sure that lines fit certain people.

And when I wrote out to everybody, I just said, “Hey, can you either sing this or just say it however you want to do it? But can you send this back? And I'm gonna split it up and stuff.” And it was funny because you could tell some people were going straight from the record because there'd be the pause and then they'd start up again kind of thing. Like our friend Julie [Carroll]. She was married to Mike Carroll [vocalist for Poison 13]. She's fourth generation Californian and she did learn punk rock in Hollywood. So she's got that line. Beth’s got the line, “punk rock changed our lives,” you know, ‘cause it did. And even now, if I start talking about it, I kind of get choked up. And I remember John [Doe from X], like writing to me right off and just when he heard it, he was the first one that wrote me back and said, “I’m in.”

And then as soon as I sent it out to everybody, once I got it done, he wrote me and was just going, “I was tearing up.” And I said, “yeah.” It kind of turned out a lot more powerful than I imagined it in my head. It's pretty great. I'm super proud of it. I'm kind of surprised it didn't get a lot more press than it did. And I'm not meaning that in such a way of like, “Oh man, nobody wrote about it.” You know, I kept thinking of it as a thank you back to them for writing something like that about that period of time and how we all felt. And I'm surprised that a lot of people didn't connect with that strong enough that they didn't write something, there wasn't more press about it or something.

AV: Well, it's very poignant. I mean, that's one of the quintessential songs from that time period to really sort of encapsulate what punk meant to people like you and to D. and everybody. And to hear it being flipped on its head into old timey music is really cool because again, there's a DIY spirit to that too, that's very much in line with it. People had nom de plumes in blues and everything else in traditional music that weren't real names. You know, “real names be the truth.” But it's really cool to see that and then just to have it with Mike doing y'all's song, I thought, what a cool record.

TK: Well, the other thing too, that's pretty funny about it, because he mentioned it earlier is “Ducks On The Mill Pond” is in it.

JH: Yeah.

TK: Because at some point we were playing and stuff, and I don't remember what, how I figured out that like, “Oh, wait a minute, that totally works.” So like we threw “Ducks On The Mill Pond” on top of it. You know, it keeps kind of building up is what happens. And then when it really gets built up, you'll hear “Ducks On The Mill Pond” on top. So that's pretty great.

(Up Around The Sun’s cover of The Minutemen’s “History Lesson (Part II).”)

AV: That's hilarious. Really, really cool. And Tim, I was just gonna ask you in terms of your visual art, which has this folky quality to it, is there some sort of coinciding of this era of your music and that in your mind. Or have you always been doing all of these things?

TK: I've done art and music since before elementary school. I’m sure art was probably the first thing. Probably a crayon or whatever. I’ve just always done this. Taking photos and all that kind of thing. So like, I never, ever quit. It's just that when all the band stuff was going on I was doing more posters and album covers and things like that. I wasn't painting big things. And when I started getting asked to do it again, I kind of started thinking about the whole idea of how people will come up to me and talk to me about the older bands— or this, that, and the other— and it really influenced them. I realized that we all influence somebody and you just don't even realize it. And like, if this comes out [video chat], like we're doing right now, FaceTime, I don't think it will, I think you're writing or whatever. But somebody could literally see the shirt you're wearing and go buy that shirt. You just influenced somebody. And when I started thinking about that, I started thinking, you know, if I'm going to start painting again, I think what I want to do is I want to paint people that really influenced me. And then I kind of hope that maybe they'll look up somebody or something. Or, you know, they'll realize that here's a sports person, here's civil rights, here's jazz, here's music, but they all were doing what they were doing because something needed to be done at that particular point in time. And so that means all of us are capable of something like that happening. So that's kind of where it came from and now it's just kind of grown into this really big, huge [thing].

‘Cause I always like reading about underdogs and all this kind of stuff, and I'm finding out more and more and how things are connected. Like the thing in Birmingham that's so great when we did that big, huge mural on the side of the Firehouse [Community Arts Center mural of Sun Ra, civil rights photographer Spider Martin, Angela Davis and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth]. I'd already met Tracy [Martin], Spider Martin's daughter. So what I did was, she knew we were doing this stuff and everything, and literally when I had painted it— and it had been raining all that week and it was nuts. We didn't have a lift. We just have ladders. So you're 40 feet up on this crazy ladder when it's raining and painting this thing, and right when I was writing Spider Martin's name on the bottom of it— because I'm always really into people coming and being part of it so that they would come back years later and be like, “Oh yeah, look what I did! I helped.”— I hear this beep, beep, beep. And this truck comes flying into the parking lot. And it's Tracy and her mom. And I’d never met her mom. And I was just like, “Get out, come over here!” So she finished the name and then handprints, which I bet a bunch of people don't even realize the two handprints on the bottom are her mom's and hers underneath Spider Martin. And that kind of stuff, I really, really love. I really like where things get connected and stuff.

AV: Well, I mean, I'm seeing this Spider Martin print right next to you here.

TK: That's because the first time I had a show, it might've been at Seasick. It was at a record store in Birmingham. I can't remember. Maybe it was Seasick. I have no idea. I can't remember where the first one was, but I knew that she lived there [Tracy Martin]. I hadn't met her yet. And I knew that she lived there through friends. And so I painted Spider Martin, and I was hoping that she was going to show up. It was around around Christmas and I was hoping that she's going to show up. And art is so subjective that you either like it or you don't, it's not going to offend me one way or the other if you don't like it or whatever. But if you like it, and it's your dad, take it, it's yours, I'm celebrating your dad here, thank you kind of type thing. And so she didn't show up, but [Jonathan] Purvis did. And I didn't know him at the time. And he walked up to me, and he goes, “Is there any possible way you would trade for some Spider Martin prints? Trade me that.” And I'm thinking— I didn't say this to him, but in my mind, I'm just thinking— man, I'm really hoping she shows up, because I want to give it to her, but sure. And I mean, literally the first thing out of his mouth, it was so frickin’ great, it was like, “Man, this will be the best Christmas present for her ever.” [laughs] And I just went, that’s the best.

JH: I’ve never heard that. That’s great.

AV: That's hilarious. Well, I'm curious, in terms of like influences, were there some common people and inspirations for you all from old-time music that you all sort of coalesced around, or has it just been this open conversation through music?

TK: I mean, I've been learning more about it from them than anything, because I didn't really know about Tommy Jarrell or things like that. So I got into all this stuff. I now realize that Taj Mahal on this one really great song that I think’s on Sounder Soundtrack, or I can't remember, but anyway, it's him clawhammering. And I didn't really know that. I didn't really understand the difference. I just knew that whatever that is, that's really cool. I didn't know if it was still bluegrass picking or what it was. So then when I kind of heard that lope and saw them doing it, then I realized, “oh no, wait a minute, this is a total different kind of thing.”

JH: I would say that the tunes we do are kind of all over the place. There's no real idea behind it. I will say on the very first record we did I pulled out the weirdest old-time tunes that I knew, that I loved, but I never got a chance to play them with anybody, you know? And then Tim, he'll play anything, and he figures it out on the spot. So, I get to play “Ben Lowry’s Reel.” It's a weird, obscure tune. And the person I learned it from passed away and nobody knows it. Tim doesn't care. He just listens and starts playing the chords. Anyway, it started off me kind of going deep into the stuff that I love, but that I didn't get to play with anybody else. But now we do a lot of real basic simple tunes.

TK: Well, just because it’s like what I'm doing changes it. And not on purpose. It’s just because I hear it like that. It's funny, I mean, there's stuff in Irish music, there's a— I can't believe I can't think what this fiddler's name is— but he's the one that kind of came to America, went back and recorded. And his recordings are, there's a guy playing piano, and there's a lot of times on the piano where he's not doing the right chord or he's just like so locked into the 1-4-5 kind of thing that he's not. But “that's the way it's supposed to be played because that was how it was on this” kind of thing. And I don't come from that. I don't know how to explain it other than it's not like I'm thinking, “oh, I'm going to change what all's going on.” It's just most of these things all came from Scotland and Ireland too. So it's kind of like, I don't really understand why in Irish music the guitar is tuned to DADGAD. I'm tuned to DADF#AD, because I came from Richie Havens and all that kind of stuff, so I don't really understand how in old-time that they didn't have guitars tuned to that too. You know what I'm saying? Because it's just odd to me, but it's just the way I hear stuff because of what I came from. How I hear things come to me from the history of what I was listening to.

(Up Around The Sun.)

AV: Has that been fun for you, Jerry, to have that new sort of mindset to work off of?

JH: Yeah. I’m constantly surprised by something that Tim does in a pleasant way. You know, even before we logged on to talk to you we were playing and recording some tunes. I just hear something different every time. I will say something about the music: a lot of it is from the British Isles. But when it got over to the New World, it was intermixed with African music. And the banjo is an African instrument.

AV: Yeah! Right.

JH: We don't do a lot of things of African descent. There's a new “8th of January,” it's from a Black fiddler.

TK: Yeah, that's a good tune.

JH: Yeah. But some of those we're asked about are very bluesy, repetitive. So it is Ireland and Scotland, but also Africa.

TK: Or just like a melting pot of stuff when they got over there, so yeah.

AV: For sure. I was curious how the live album from 309 came about. The punk house in Pensacola.

TK: Oh, that's ‘cause the guy had been writing and stuff and wanted to see if we would record [Derek Atkinson, engineer]. I mean, there's no preparation for anything. We just sit down and start playing. And he wanted to do that. And I said, “sure.” And I had a residency there for about a month. In the summertime we were there. So that's how that all went down. And then we made sure that he put it out, but it was going to help them. You know, help that place kind of keep going and stuff. So once again, community.

AV: It's a great thing that they're doing down there. And again, it’s sort of part of the organic nature of all of this, right? And that community, but also this DIY organic reaching out to people and little sparks fly off.

TK: And I will say, ‘cause you just said it, which is great. You said DIY kind of thing. Because I kind of was going on about saying the punk house kind of thing— or 309, I think it was a punk residency thing— because I kept saying, “You really ought to change that to DIY, you know, because punk is so not what it was.” It's just such a uniform and set of rules and all this stuff. And it's just like beatnik or hippie or any of that stuff. Like when it first started, it was just a bunch of people that got together and it was like, “Well, we can't do this here, can't do it here, we're gonna do it over here. If you want to come, come on.” And then all of a sudden it gets a name, it gets a uniform, starts getting all these rules which has nothing to do with it. Like for the longest time I could never really quite understand why Jack Kerouac had such a problem with the whole beatnik thing and he didn't really like being called that. But now I totally fucking get it. Because it's like, the whole punk thing to me is just like, no, we weren't doing that. We were doing DIY. So yeah, same way. I kept trying to get them to change it, so people wouldn't box it in. If they heard DIY, it's coming more from the spirit of what this all was and still is.

AV: For sure. Well, finally, you're going to Japan. How exciting is that to go over there and play? And how did that come out?

TK: It’s great. I love it over there. I'd move there in a second if I knew how to speak the language. [laughs]

JH: We had a great time. We were there last year, a year and a half ago, where we met Bosco. I've been there once before, so I have a some familiarity with it. But it's so much fun to be doing this with Tim because he's been there for art shows as well as music. So meeting Tim's art friends and music friends in Japan, it just opens up the world. And people say, “You're taking a banjo to Japan? Do they hate it?” But the people we meet just like music and they like creating things. It's part of the family. It's just a different part of the world.

TK: Extended family.

AV: Well, I’m really excited for people to hear this album and hopefully this will get people to listen to it and check it out.

TK: Yeah, we just got some crazy review from Holland. He hadn't seen it. I'm going to show him, but there's not a whole lot of people over here that’ve been reviewing it. We could never even get the [The Austin] Chronicle or anybody here in the hometown to do it. Which is crazy. It's weird because if people don't really know me, they'll take this a completely different way. As opposed to being something that's more coming from reality and an educational thing, where they think that if you're on the cover of something, or you're in the hall of fame, or blah, blah, blah, that the doors wide open, you've got it made, everybody's going to write about you all the time. It doesn't work like that. That's not how this works. Mudhoney— at the height of Mudhoney— they're all working at Fantagraphics, stuffing comic books. You're not getting some big house and all this kind of stuff. So the same thing here. People don't really realize that like, yeah, Hall of Fame twice, all this kind of stuff in Austin. “You're a legend! Blah, blah, blah,” kind of thing. We couldn't get anybody to even write that Bosco was here. And Bosco’s a big freaking deal for the old-time stuff, you know? So is it DIY? It’s just like do stuff on your own and do stuff. And here you go. I got called an “outlier,” which I didn't know what the hell that was, and I looked it up and realized that it was like somebody that's just doing what they do, and you know, just walk your own walk kind of thing. I was like, alright, Sun Ra, here we are.

AV: Well, that's actually a great space to be in because you don't get defined. You don't get pigeon holed, you don't get the uniform, you get to be whatever you want to be.

TK: And plus, you better be doing this stuff because it's coming from the heart, and it's something that you really like— any of the self expression stuff. Because in the big picture, it's gonna end up being you and yours. And I'm not even sure how to explain that, but you know what I'm trying to say. If you're trying to do it to please somebody or to make a name or make money or any of that kind of stuff, you're going to have a really, really fricking hard time and it may never even happen, you know? So you better be doing stuff that you really like and like that you are fine with.

AV: Thanks so much for the fascinating conversation.