Reversed Lens, Pt. 2: An Interview with Michael Macioce

Reversed Lens, Pt. 2: An Interview with Michael Macioce

(Michael Macioce portrait, 2021. Photo by Jesse Lizotte.)

What follows is the full interview from the most recent piece I wrote for Aquarium Drunkard about the great NYC-based photographer Michael Macioce, tracing the arc of his remarkable career from his earliest days as a teenager falling in love with album cover artwork— and the photography that went along with it— to making his way through the vanguard of contemporary underground music, becoming a teacher, and then recently finding renewed interest in his work again through Instagram. It’s a really amazing conversation that covers several eras of modern soundmaking, its visual accompaniment, as well as a host of related topics about contemporary art, media and education. If you’re a fan of his work, or just music history in general, and the redemptive arc of the internet, there’s a lot to love and sort through. Enjoy!

- Lee Shook, aka- The Audiovore

AV: I wanted to start off by asking you a little bit about your background, and particularly your love of music. I know your older brother was a member of the band The Brooklyn Bridge and had an influence on your tastes growing up. Did you grow up in a musical family?

MACIOCE: No, outside of my brother. I mean, my Italian-American father, who grew up in a family on Mott Street in Manhattan in 1920, he was born one of eleven children, and they all played a musical instrument. So, in that sense, what happened with Italian-American immigrants at that time was they brought a love of music over. You know my brother likes to talk about how the guitar really was an Italian instrument, and these Italian-Americans came to Brooklyn and began to teach kids guitar, and then the electric guitar came out, and there's sort of a connection there. So, I think that the New York City immigrant roots are partially the background for people loving music in New York. And like the different immigrants— we had the Jewish music that was going on— and all these cultures really mingled. So I think that's where the guitar players start playing electric guitar and then all those rock and roll shows come around to New York. I can't remember the name of the guy that brought all those big rock and roll extravaganzas with Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis, like in the movies. And I think if you had roots in the Lower East Side, even if you grew up in suburbia, music was really key.

AV: Could you talk a little bit about your brother and The Brooklyn Bridge and just how much of an influence he was in terms of your own musical development?

MACIOCE: My big brother [Richie Macioce] got his first guitar at 10 years old. The other day we were talking about Duane Eddy and the twangy guitar and that's where my brother’s roots were. So my brother kind of came out of that love of the guitar, and by the time I was 10 or 11 years old he was traveling with The Brooklyn Bridge appearing on television on The Ed Sullivan Show and I got bit by the bug. When you see your brother on The Ed Sullivan Show and everybody in school is talking about it that's what you want to do. So I took a few guitar lessons from my brother, and then all of a sudden he was 23 years old and moved out of my parents’ house. And that's when I picked up the camera and said, ‘You know what? I want to make record album covers.’ So, I think I was always a little more of a visual person than a musical person. And it was kind of my fate to want to do record covers. My brother had a real collection of albums. He had a reel-to-reel tape player. I remember when he got his Ampex reel-to-reel and he made me come inside of his room and he played the Beatles’ White Album, which had come out probably six months before, and I can still hear “Dear Prudence” fading in in such a clear, perfect sound that a reel-to-reel tape would give you. So, my brother allowed me to experience the auditory effects of a great stereo, and taught me to play guitar, but also had an extensive record collection. Another memory that's clear in my mind is looking at the cover of Procul Harum’s A Salty Dog and being fascinated by the cover. But not just the salty dog part of it, but the big round life preserver, I think it was, that was part of the cover. And I thought a lot about how records are these like round things and these square covers. I was always interested in how it was a round record and a square cover. And when the Shockabilly records were made, I had this idea, how about using the saw blade solarizations that I did in my parents' house with my dad's saw blades from the saw and I solarized them and we used them for the record labels.

(Album cover for Shockabilly’s Vietnam, Fundamental Records, 1984. Cover by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): So it was from looking at those record covers. I can remember looking at Jethro Tull's Stand Up and seeing the cutouts stand up when you opened the record. So it wasn't just hearing the music or that my brother was a guitar player. He had all these albums that I would just stare at. And then as I became interested in photography and would buy the popular photography magazines, inside there would be Nikon advertisements, and the Nikon advertisements at that time featured a photographer named Pete Turner, who was an experimenter with color photography. And Pete had done all the records for the CTI Jazz label— if you remember any of those record covers, Bill Evans’ Montreux and this really beautifully colored Joe Farrell— and my brother had all those records. So now I'm seeing that all of those cool color record covers, it's this guy that's inside of the photography magazine. When I was about 25 I wound up getting referred to assist Pete Turner. I can remember going in and meeting the assistant, and I said, “You know, I always loved looking at the record covers he did for CTI Jazz.” And the assistant looked over at me and said, “You do, huh? Make sure you tell him that.” So, I really wanted to do record covers. So I guess that's what I'm saying about the influence my brother had was not just musical, but allowed me the opportunity to delve into the visual connection. When people would ask me later about influences of my photography, I would say the Beatles. I would say Fripp and Eno's solo records, more than photographic influences. I wouldn't say Ansel Adams or something like that. I would have said Man Ray was probably my photographic influence. I was doing solarizations when I was in high school, so to me, the connection between music and the visual ideas that go along with music was what interested me. I'm kind of half a musical person and half a visual person. If I was more of a visual person, I probably would have been a big advertising photographer or something like that. But that's not what I wanted to do. I wanted to go photograph bands and touch my heroes by having the opportunity to take their picture for an hour.

(The Brooklyn Bridge performing their cover of “Worst That Could Happen” live on The Ed Sullivan Show.)

AV: Didn't you get to meet Chuck Berry when you were very young?

MACIOCE: Yes, I did. Oh how I wish I would have taken his picture. I got his autograph instead. It was in that era they had all these nostalgia shows, but by that time— by 1977 or so— the doo wop, rock and roll era had aged out. And I say aged out because it wasn't the kids going to the, like, Alan Freed shows. Alan Freed did all those rock and roll shows. Well, all those kids eventually grew up. And by the time I came along— taking pictures in the middle-70s, late-70s— these grown ups aren't packing colleges to go see these bands anymore. But they do go to supper clubs and pay a lot of money to sit there and have dinner. Kind of like New York City had The Bottom Line. So there were these nostalgia shows and I got to meet Fats Domino and Chuck Berry in the same day. To give an anecdote about my brother, he was on the stage when Chuck came up to play and asked my brother to play the piano— he could play a little bit of piano. And there was another guitar player there and he played the song “Kansas City.” And my brother said, “Wow, you really can play that song! You play it really well.” And the guy said, “I oughta. I wrote it.” So, that was an era where you'd get a chance to meet people like the guy who wrote the song “Kansas City,” for god's sake. So, I was young enough to touch that. So yeah, I got to meet Chuck Berry. I got to be right in front of Fats Domino at the stage and take pictures of his bejeweled hands. I started out with those guys and I finished up taking pictures of Pete Seeger and Odetta. I was in my 50s taking Pete's picture, and the New Lost City Ramblers were there and Arlo Guthrie was there, and I realized, wow I spent a whole life doing this type of photography and here I am with Pete Seeger. It made some sort of completion. I felt like, okay, I did it. Because, you know, you don't make a lot of money shooting pictures of musicians that are obscure. And I always felt like I was not a professional because I was making my money elsewhere. But when you're 50 years old and you realize you've been doing it this whole time, there's no other conclusion except this is what I am, this is what I've done and glad that I'm still doing it. I never did get around to making a lot of money. My friends that were school teachers are much more secure now that they're in their 60s. But I wouldn't trade the lifestyle. I wouldn't trade it back. It's moments like this where I get to tell the stories I realize just how valuable, as opposed to money valuable, experience is.

(Fats Domino live at Madison Square Garden, 1975. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

AV: I was gonna say, you got to shoot some legendary artists very early on in your career starting in the late-70s, from groundbreaking jazz musicians to prog rock bands. Who are some of the first artists you covered and how did you get access to them?

MACIOCE: There was this time period where I kind of was moving out of just going to shows as a fan, to going to shows photographing my friends who were in some of these bands. Like Kramer started working with Allen Ginsberg, so I got to take Allen Ginsberg's picture, for example. People in my age group began to work for the heroes, so to speak. So, it might have been I go to Hurrah’s one night to photograph my friend's band, which was the Swollen Monkeys, right? An Ohio vehicle— Ralph Carney and those cats. And playing that night was James “Blood” Ulmer. So I got to photograph Blood Ulmer because my friends were there being the opening act. And in between the acts I go walking backstage to see my friends from the Swollen Monkeys, and who do I run into coming out of Blood’s dressing room? Sun Ra. Sun Ra came to watch James Blood play. And Sun Ra was in full regalia as a visitor. He wasn't even playing and he came out to go to a club dressed as Sun Ra, of course. So there was this in-between period where the young people were playing gigs where the old masters were also playing. That same night in front of the stage, I’m taking pictures of James Blood playing and my friend says, “You know, there's a lot of people here today. Other musicians.” And I said, “Really? Who do you see?” You know, I got my face to my camera, trying to take James Blood’s picture. And he said, “Well, Robert Fripp is here.” And I said, “Really? Robert Fripp is here? Wow, that's cool!”— I'm snapping away. I said, “Where is he?” As I take the camera away from my face, Randy says, “He's standing right next to you,” and I turn around, and Robert Fripp was hanging on the stage just like I was. He was there to see Blood play and I was there to take his picture.

AV: Even before that I know you got to photograph people like Van der Graaf Generator and Frank Zappa.

MACIOCE: That was firmly in the fan years. We were high school students. And what I'd say about the Van der Graaf gig— at the Beacon Theatre I think that was— it was the only time they played New York. I took great pictures of them. That was an era [when] it wasn't like they put all the professional photographers in the pit in front of the stage. At that point, fans could get up from their seat and run up to the stage and hang out for a little while and take pictures and then go back again. And I made the most of that opportunity wherever I was. I'd say, ‘Okay, I'm going up there now.’ I'd meet my friends sitting up there and I'd go up to the stage for a while. And that's what I did with Van der Graaf. And you know, I loved my pictures. They were good pictures. But I never thought of trying to sell them or anything. I was 17 years old. But then when I published those pictures on Instagram a few years back, some author that wrote a book about them contacts me and said, “Well, you know, I'm in touch with these guys all the time, and they told me that they wish they had seen your pictures back then because you took the best pictures of those gigs.” So that was immensely satisfying. And that, in a way, connects to the desire that we all have of a chance with the music to find something cool that nobody knows about. You kind of get passed a little bit of that coolness because you found out about this music. There’s something satisfying to know that, all those years ago, I took the best pictures of Van der Graaf Generator, and yet it's not until everybody's old and retired that I find out about it. It’s kind of like part of the secret.

(Peter Hamill from Van der Graaf Generator live at the Beacon Theater, NYC, 1976. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

AV: It’s sort of bearing witness to a lost history that doesn't become important until later in retrospect, which is a really amazing full circle moment, I’m sure.

MACIOCE: It also mixes in with the struggle part, as well. I mean, I did get a chance to photograph a lot of musicians at the beginning of their road. And then they have their moment in the sun, and I might have taken pictures of them when they were young, but the record album cover that the photographer gets $20,000 for goes to the famous photographer of the day. So, that's happened to me before. I can remember that happened with Matisyahu. I took pictures of Matisyahu in Crown Heights, Brooklyn before anybody. Nobody knew him. He was just another Orthodox Jewish person in a whole neighborhood of Orthodox people. And then a few years later, he's a big star, gets signed to Electra, and the guy got paid big bucks to shoot his record cover. And I wound up selling my pictures to them for $500, right around the time the guy got signed. They got the pictures from me for a little bit of money and I found out that the next guy got $20,000. I called up Kramer and bitched to him and I said, “You know, it's just so depressing to see the job go to someone else when I was there first and did great pictures too. My pictures were just as good as the famous guy's pictures.” And Kramer said, “I wouldn't worry about it. I'd wear it as a badge of honor.” And that really helped. I have a lot of honorable badges, but without the security. Every now and then you see they're doing a benefit concert with some musician that you know and love but didn't have health insurance. You know, notable people. It’s not a secure industry, whether you’re a musician or a photographer.

(Matisyahu, Crown Heights, Brooklyn, 2005. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): I can remember talking about this subject with Peter Blegvad, who had come to New York, and he came and we met each other on the Lower East Side and we went out to lunch. He was kvetching about how it's not a very well-paid industry. Peter said, “Well, the word art has its root in the word amore, which is ‘love.’ That's why we do our art.” And that helped, you know, along the way. And that's what these interviews are good for for me, as I remember things that people say, and I realize those axioms and adages really take on a meditative power. They're talismanic. This is where it’s a badge of honor. It really helps have a truce with the struggle that doing something creative in a way that you think is unique is about. Later on, when I was an assistant to the civil rights photographer Bob Adelman— Bob was on the steps with Martin Luther King for his “I Have a Dream” speech. Bob photographed everybody. He was one of the Warhol photographers, gets a big credit in Ciao! Manhattan about Edie Sedgwick. And looking at my pictures, he was like, “Well, you know, now what you have to do is get people to care.” So, at that time, I realized it's going to be really hard getting people to care about some of these obscure musicians, to care enough to make a difference in my life. But now, here I am with a bit of a second act with my pictures from this era. And no one else can go back now and take pictures of these people. That's gone. I have these black and white photographs that were taken in an era that it was a lot of work to take and make photographs of folks that were under-documented in a time that they were doing their greatest work. It’s very consoling that I took those pictures, because it is a trade off. I don't like talking a lot about what a struggle it was, but it really was, and I don't know how to be truthful without talking about it— how paying your rent with the money you made on the publicity photo shoot is hard to do. This month's rent that I’m behind on.

(Kramer at Noise New York, 1988. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

AV: I wanted to back up a little bit and talk a little bit more about your relationship with Kramer from Shimmy-Disc and Bongwater. You grew up with Mark. I was wondering if you could talk about your relationship and what it meant for your life in terms working with him on a lot of different projects, records, and going on tour with him with Shockabilly. I was wondering if you could take people back to meeting him and just what kind of influence he had on your life.

MACIOCE: I’ve probably known Kramer since fifth or sixth grade. He was literally around the block. Like, if I were to walk through my backyard into the next block and cross the street, I would be at his house. So we went to school together. He was always an alternatively-styled person, shall we say. He was a weird kid with a trombone, and I was a rock and roll kid, and he’d get on that school bus every day with this big trombone case, with his frizzed out little afro-type of hairstyle, and one day we just started talking about music. I don't know if it was the trombone part that got us to talk, but we just started sitting next to each other on the bus every morning and we'd talk music. Then we started hanging out with each other. And we would just, you know— “Here's music I got turned on to. What do you think of this stuff?,” that I would get from my brother. And we'd sit in my brother's room and listen to some of those records. And as we kind of veered from being prog rock boys— listening to like King Crimson when Lark’s Tongue in Aspic came out, before the later records even came out—we found out about Eno. I went into the Sam Goody record store one day, and I'm going through their prog rock albums, and I see this really weird album with a weird record cover by Eno. A guy named “Eno”— I had no idea who this was. But look at this record cover! Oh my goodness! And I turn it over and I'm reading the credits and I see Robert Fripp’s on that record. It's like, oh wow, how interesting. And so I bought it. The same day I bought that record, another one I bought without listening to it was Neu!. It was Neu! ’75. So, on the same day, I got two of the records that most influenced me as a fan. And I bought them both without knowing what the music sounded like. It was just kind of like, look at this! This has one musician I know on it. This is interesting. And I would bring that back, and Kramer and I would listen to it, and all of a sudden this whole world opened up where then the Fripp and Eno records were quickly found by us. And a couple of years later— we're now like 18 or 19— and Lucas Samaras had an exhibit at MoMA where the mirrored room that was used on the No Pussyfooting record was. And we got ourselves into MoMA and got to sit inside that mirrored room like we were Fripp and Eno playing cards. We were still kind of kids, you know, playing. I can remember closing the door to the mirrored room and you were in complete, total darkness, and they let you go in and do that kind of stuff.

(Fripp & Eno’s No Pussyfooting album, 1973.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): So we grew up as boys, as teenage boys, goofing around playing tricks on each other, dropping acid and listening to this music. And in the 1970s, it was really easy to want to tune out from the real world and immerse yourself in this strange world that rock and roll had turned into and be that person. So we both did that as high school students, and then shortly afterwards we went off to colleges, and we didn't see each other for what was probably a summer. It seemed like forever, but then when you're young, a summer away from one of your friends that you spent a lot of time with seems like forever. And then we got back together again after one year of school, and we realized just how we were both having similar experiences. He was up at CMS [Creative Music Studio] meeting these musicians, and I'm in Manhattan going to the School of Visual Arts going to see the Philip Glass Ensemble play. I was doing things like, I had a little bit part in a Jonas Mekas film downtown, because that's what my teachers were doing. My teachers were immersed in that residue of the New York Berkshires psychedelic scene. A lot of the teachers in the city teaching in the art schools were part of that summertime up in the Berkshires thing— at least in the 1970s they were. And I had a teacher that had worked with John Cage on a project with Marcel Duchamp. So, there I am, 18 years old, and realizing what they would later call the “six degrees of separation.” You could have a teacher that's a relatively young person who worked with a master like John Cage, who was getting an opportunity to work with the founding master, Marcel Duchamp, and you really did have a sense that you belonged to this— I guess we were using the word “postmodernist” at that time. I can remember in my art history class, Anne Sargent— who was a pretty young then, but a distinguished art teacher and historian— she was writing for a newspaper called the Soho News. And I can remember her showing us some of the postmodern work. I can remember looking at one concrete cube, I think it was by Carl Andre, and she was saying, “You know, not even we're sure if it's art.” So, being part of this postmodernist thing where La Monte Young and Harold Lamont and the Velvet Underground kind of connected with Yoko. And I had a sense as a teenager that I was part of that.

AV: That's an amazing legacy to be a part of and something that I'm sure is incredible to sort of look back on now.

(Karl Berger at Creative Music Studio, Woodstock, NY, 1978. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

AV: You know, I wanted to finish up the the thread with Kramer in terms of you working with him after growing up together and then coming back around and touring with Shockabilly, which I know you did a couple times with some European tours. And doing a lot of work for Shimmy-Disc doing the artwork for record covers for so many great bands. I was wondering if you could talk about where that sort of lead you.

MACIOCE: I had been in the city for a few years when Kramer started performing with Chadbourne and Zorn and those bands like The Chadbournes and Country Western Bebop. And then that kind of led to Shockabilly. Then Kramer and Eugene asked me if I wanted to be the fourth person and come on the tour and be roadie/soundman/photographer all wrapped up in one. Boy, was I a lousy soundman. But I guess with Shockabilly putting reverb on the vocals it didn't really matter as much. Later you don't do such things. Then Shockabilly broke up. This is interesting— it’s not so much about me, but a little bit more about Kramer. I guess it gives a little insight into how we were feeling our way along. So Shockabilly breaks up— Kramer and Eugene had some sort of argument or something like that— and I'm sitting in Kramer's apartment, and he's like, “What do I do?” And around that time, Kramer had gotten an offer to go be the keyboard player in Joe Jackson's band. And I said, “Why don't you go take that job with Joe Jackson's band? That sounds like it'd be a lot of fun, right?” And Kramer kind of looked at me and he thought about it, and then the next thing I knew, he bought a recording studio [Noise New York]. He wasn't going to go be a sideman, even if it was for Joe Jackson, who was doing really big hits at that time. He wasn't gonna go do that. If he couldn't play in one of those bands, he was gonna release everybody else's band. And that's how Shimmy-Disc got its start.

(Shockabilly, London, UK, 1983. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): So Kramer starts Shimmy-Disc— well, first he started buying Noise New York from these two cats that were up on 34th Street. He bought a recording studio and he began to produce some records for the Lower East Side musicians that we were getting to know. There was a Shockabilly gig at a place in Midtown called Tin Pan Alley, and Kramer said, “I want you to meet somebody. He lives on the Lower East Side like you do.” And it was John S. Hall. So I can remember I was introduced to John at a Shockabilly gig— he had really long hair at that time— and I can remember sitting with him. So I began to meet some of these musicians that were going to be the people recording on Shimmy-Disc. That first record— The 20th Anniversary of the Summer of Love was what it was called— and it was all these samples of people that Kramer was going to put on his label, which included Christian Marclay. That's where I got to meet Christian Marclay. So that first record was a compilation record of all these artists that were going to have their own records. So I began to photograph all those people— the guys from Sharky's Machine, Christian Marclay, what would become King Missile— a lot of the musicians from that first record. So that's how Shimmy-Disc, being such an eclectic label, was my opportunity to take pictures of these musicians. And since Kramer was responsible for producing the records, and having the records pressed and printed and distributed, they needed record album covers. And these bands didn't want to pay for their record album covers, so Kramer would ask me for pictures. And at that time I was wandering the neighborhood looking for record album covers. And I wasn't looking for actual covers. I was looking for ideas, photographs. And I began to take pictures of reflections in windows in a neighborhood that was an alternative neighborhood, so you got some pretty weird windows. And so that's where I got all those record covers from. I got the opportunity because they needed record covers and nobody wanted to pay for them. And I got to fulfill my dream of making record covers— creative pictures, not just insert pictures of bands— by doing so. That's what I would say about that period of early Shimmy-Disc and how it related to me taking pictures and meeting those people and taking the pictures that became the dream record covers that I wanted to do.

(Bongwater’s Breaking No New Ground! EP on Shimmy-Disc Records, 1987. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

(Bongwater’s Double Bummer LP, 1988; B.A.L.L.’s Bird LP, 1988; King Missile’s The Way to Salvation LP, 1991; John S. Hall & Kramer’s Real Men LP, 1991. Covers and photographs by Michael Macioce.)

AV: You got to work with people like Galaxie 500 and Butthole Surfers, who have a Kramer connection, as well. There was a really vibrant scene happening around New York, but a lot of great bands were coming through, too, that you got to work with.

MACIOCE: There's two ways of looking at it. One way of looking at it is it was a very vibrant scene. Everybody has their vibrant scene, and it's more about you happen to be young at that time. That's an egalitarian way to look at it: is everybody's scene is no better, no worse than everybody else's scene. But I don't know. I think the Renaissance was probably better than the Dark Ages, right? I am a Dark Ages fan, and new history fan, but nevertheless I think there was something special about that time. Years ago, I think Magnet interviewed me for a Kramer piece, and the guy mentioned how I was a good representative because I was part of the zeitgeist of the era. And at that time, I was like, well, I don't know about “zeitgeist.” I thought that was too big of a word to use for this rock and roll fan that was just trying to take pictures of what's going on. But the more time that's gone by, the more times I do things like I'm doing right now talking to people about it, or just tending my Instagram, I realized that it really was a zeitgeist for the 1980’s in New York. That was a good time. Even taken from the position of everybody gets to have a good time when they're 25 years old and going to all the gigs and trying to take pictures, or whatever role people have in the creative arts in New York, and not just music. You know, you could be an assistant to a painter. The work I did with Bob Adelman as his assistant, we'd go down and photograph Roy Lichtenstein in his studio, and then we'd all go out and have lunch. I can remember passing around my book (Light & Dark, 1992) at a Roy Lichtenstein lunch. Bob was like, “Why don't you show Roy your book?” I took the book out and Roy's thumbing through it, and he hands it to his first assistant. And the first assistant's like, “Oh my god, the introduction’s by John Zorn?” Like, the assistant knew everybody in the book. And Roy and Bob were just kind of looking over really pleased that their assistants connected on this level. I came home that day and told my girlfriend about how I had lunch with Roy Lichtenstein. And then a couple of years later Roy died.

AV: I wanted to ask you about another band from the Shimmy-Disc family you got to work with early on and had some unique adventures with, which is Ween. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your relationship with them as they matured— if you can call it that— and developed as a band. But also just some of the adventures you got to go on.

MACIOCE: Ween was one of those bands that, when Kramer became famous— and he became famous when Rolling Stone decided he was the producer of the year one year— and I can remember going to Kramer's apartment after he became the producer of the year, and there were three giant sacks of mail. You know, those great big 50 pounds of potatoes kind of sacks of mail— that's how much mail he got after being the producer of the year. And it was not all bands sending in their tapes. Sometimes it was like people sending in nude pictures of themselves and things like that. But for a while there, he'd call up and say, “Come on over, I got something in the mail today.” And I'd go over there and I can remember one time I went over and it was a video from GWAR. Never heard of this band, and then I'm seeing this GWAR thing where they're chopping through the TV station and I couldn't believe what I was seeing. And he's like, “I’m gonna sign these guys.” And then another time, it was like, “Listen to this.” And I guess Ween had already put out God Ween Satan, but it was the first time I'd heard that music. And again, back then, when you heard Ween for the first time, it was different. You know, we're all into the music and everything, but here are these two kids that through playing records in their little basement, had established a new way of looking at the music that we came out of. It was completely new. It was like, wow, it's so fresh. It's like when you see a Jackson Pollock for the first time, you're a student. Or Marcel Duchamp's sculpture. You just laugh. Because I laugh when I'm in the presence of great art. And Ween made me laugh harder than anything. I was like, “I want to take pictures of these guys! Where are they?” Oh, they're down in South Jersey, a place called New Hope. “You think I can go down and take a picture?” And he said, “I think I can get them to do that.” So, my girlfriend— we got married by that point— she was a filmmaker. We went down to South Jersey to The Pod, and Ween was Ween. They were dressed in like bathrobes and stuff. They look like they just woke up. So I took pictures in The Pod and then I said, “Let's go to some of the locations that inspired you.” So we went out to the field fair on the farm and then I said, “Where's the stallion? Is there a horse there?” Well, a stallion isn't a horse. A stallion's this guy. You know, it's like the ranch hand we call “The Stallion.” So, you know, I got my ass in the car and drove all the way to South Jersey. It was like a three hour drive. New Hope, Pennsylvania…Lambertville…wherever that was. But I wanted to take pictures of this band because I thought their music was really out there.

(Ween in the cornfield outside The Pod, Lambertville, PA, 1991. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): So, I made an effort to get out there, and they didn't use any of my pictures for their records. They had their own ideas. But one of the Ween fans wrote in when I posted a Pod picture, and he said, “You basically have the Holy Grail of Ween pictures here,” and I liked that. I got my ass to The Pod. No one else did. Not Bob Gruen, or Danny Fields— you know, all these great, great photographers that got to take everybody's picture early on. They didn't get there. I got there. I wanted to go see that. So, there was that, and then I go to the Ween gigs, and early enough that the third musician— crazy musician— was still with them. I don't even know if he was a musician. Larry— that's the guy's name. He was really weird. I think Larry was probably a little too high to stick with the group. But there was that stuff as well, and then some stuff in the studio. Kramer was in Noise New Jersey [by then], so that's interesting to think of. Because I heard the Ween music at Noise New York, when he was downtown. But by the time they came to New York, and I took their picture in New York, Kramer had moved his studio. I don't know if that is of interest to you, but it's of interest to me to think about it. That was right in that little envelope of time between when Ween sent the tape to Kramer and when Ween was in their recording studio.

AV: Didn't you go to Jamaica with them one time?

MACIOCE: Yeah, what a trip that was. That was like the movie The Year of Living Dangerously. You just don't know if you're gonna get clubbed over the head and wake up on a steamer to some place. It was a real dangerous trip with these real outlaws that were down there in Jamaica.

AV: Can you recount some of your adventures?

MACIOCE: Yeah, the ones that I can remember. That's what I like to preface it with, because there was a whole lot of weed getting smoked, because I was a big-time weed smoker. And Kramer, by that time, was famously a huge weed smoker, and I don't even have to talk about what kind of smokers the Ween boys were. So we're all down there— I guess that's why we decided to go to Jamaica— the purpose was to do a film like a rock and roll video [for 1991’s “Captain Fantasy”]. And I don't know how they decided…you know, we were buying our weed from these Jamaican guys at that time. So I think our connection to Jamaica was prominent, so the idea of doing a rock and roll video— and remember, Kramer is running the show, he's got the record label and everything— so, he's like, “You guys want to go to Jamaica and do a video?” So what was Dean and Gene going to say to that? They said yes! So we got on the plane and flew down and stayed in these little bungalows. I can remember playing ping pong and Mickey beating me in ping pong, which I had never lost. And I never really screwed up playing ping pong with Kramer, I beat him all the time. Kramer got a ping pong table from Noise New Jersey. So that Ween Jamaica trip happened after they moved to the Jersey studio. That's when the ping pong table became part of our lifestyle again. And besides smoking a lot of weed, we would go to the beach, and I can remember doing the video of them in the water— where they're all in the water, Kramer's in the water too, and I'm in the water— and I have the 68mm camera just rotating around. You know, things that you would do when you were stoned. Rotating around, getting them up so they’re smoking a joint on camera. That ride to the airport— that thing that you see on YouTube— was us in the van on the way to the airport smoking giant j’s. You can see for a moment the shacks on the beach where we were staying in a couple of those shots that are still available online. My son was going to college and he said, “You know, my friends are really into weed, too. They see all your Jamaica stuff on YouTube.” I'm like, “What? I had no idea it was on YouTube.” It was on the Shimmy-Disc compilation video tapes. He tried to have a video for each artist. Most of them were supplied by the artists, but that one was shot by me. I think I might have done a Bongwater one that had a lot of live footage. So, it came out on the Shimmy-Disc video compilation. The idea of being on MTV was not even a consideration. At least not from my point of view. Those are the real stories that I can remember from there. There was just a lot of hanging out. I don't know how long, maybe we were there a week.

(Ween’s video for “Captain Fantasy,” 1991. Shot by Michael Macioce.)

AV: Let me ask you about another group that you got to shoot who sort of matured and evolved as a band, but were also hilarious pranksters in their own right, which is the Beastie Boys. You did some amazing shots of them as well. How did you get to work with them?

MACIOCE: When King Missile got signed to Electra, their management group formed a little magazine— a tiny little magazine— called New Route. And New Route got to photograph some bands and got me some other advertising assignments that were pretty nice to get at that time in my life. But one of the bands I got to do a cover of was King Missile. I guess that's one of the reasons why they made the magazine, was to promote their own band. And then they said, if you want to photograph the Beastie Boys, we're doing a piece on the Beastie Boys. And I said, “Oh, great.” And they said, “We can't pay you though. We could pay you for the film.” And I said, “The film and processing will be $35.”

AV: What year was this?

MACIOCE: I'm gonna say it was 1991. Around that time they had done like two albums four years apart, Paul's Boutique and Licensed to Ill. They were promoting that record [Paul’s Boutique], so that's why they were doing a lot of photo shoots, and they show up at The Cave [Macioce’s apartment/studio in the East Village]. First of all, one of my personal tidbits was, it was the dawn of the sneaker era. And I knew they were really into cool sneakers from the 70’s. So I took a drive out to my mom's house— I probably had to take the train out— I don’t think I had my car. And I said, “Hey Ma! Do you remember that pair of maroon-colored Pumas that I used to wear in high school? Do you know where they are?” My mother said, “Did you look upstairs under the spare room bed?” There they were. Like, ten years had gone by, and there was my Pumas. So I took them, and I knew I wanted to wear them for the Beastie Boys shoot. And so the Beastie Boys get there. The Cave was a basement apartment, so I go up the wrought iron stairs and let people in. So there I am, I'm wearing my Pumas, I go upstairs, I open the door, the Beastie Boys come in, they're looking around— I can still remember how they looked around approvingly at the dilapidated East Village backyard that they had walked into. They look around, and then one of them looked down and said, “Cool sneakers.” And I knew the photo shoot was gonna go well at that point. I’m taking their pictures and all that and they had just come from a photo shoot at Interview Magazine! Michael Halsband was their photographer— a famous fashion photographer, that they get to take the Beastie Boys pictures— and the whole time the Beastie Boys just made fun of the photographer. And this friend of theirs says [in a mocking and exaggerated New York City accent], “Come do this over here. Come look at this over there…” They made me feel so accepted. They were great, those guys. And overall, for all the act and all that, they were serious students, is how I saw them. They were jokey when they were acting for the camera, but when I was talking to them and showing them pictures and stuff, it was as if you were talking to your friends in college. And I gave Adam a picture I took in India of the Sadhu, the one that was used on the King Missile cover [1991’s The Way to Salvation]. That was probably before the King Missile record came out. John Hall had first dibs on my India pictures. He was allowed to come look at my India pictures first and take what he wanted for this record idea that he had, The Way to Salvation. But I had already made some prints, so I gave Adam a copy of the Sadhu print. That's another thing that I'm really grateful for, that I connected with his spiritual side. But we also had a lot of fun doing the shoot and they made my cat [Max]— I had a manx cat, a no tail cat, you know the breed without a tail— and they wanted to pose with my cat. And I get people that write into me, “I love cats and I really love the Beastie Boys. So I really love the idea of the Beastie Boys with a cat.” So, I'm very proud, once again, in this case that I have the best Beastie Boys cat photograph. And it's my cat.

(Beastie Boys with Max The Cat at The Cave, 1991. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

AV: Another revolutionary musical figure from New York who you got to work with very, very early on, and then continued your relationship with through the 90s and onward, is John Zorn. And I wanted to ask you about working with him, because I know you shot some very early photos of him, working with some of the great improvisers of the era in the 1970s, like Davey Williams and Eugene Chadbourne and Tom Cora. People who, in their own way, went on to revolutionize music. I was wondering if you could talk about your relationship with him, working with him in the early days, and through the Radical Jewish Culture initiatives and everything else.

MACIOCE: When Kramer went off to CMS [Creative Music Studio] and I would go up and visit, they’d talk about this guy John Zorn. So I was hearing about the respect that he had as a student musician before any of the records. Then I'm back down in New York and John Zorn was going to do his first game piece at Miller Theatre at Columbia University, and Kramer was going to be one of the musicians. And I guess Kramer might have gotten that from Chadbourne, because Chadbourne did his big orchestral piece at the same time, The English Channel. And I went with Kramer to the rehearsal. Which was…we were both like really new New York people. I can remember saying to Kramer, “I know how to get to Columbia, we'll take the train uptown, and we'll just walk to the university.” Now, I'm an East Side person, and I didn't realize that if I took the East Side train to 125th Street, I wasn't going to be on the west side of the park, where Columbia was. I was going to be at 125th Street and Lexington Avenue— “Go to Lexington 1-2-5,” as Lou Reed had said— and it was that time we get off the train and we're in 1970’s Harlem. And police came up to us and said, “What are you guys doing here?” I guess they thought we came up to buy drugs. We said, “We're trying to get to Columbia University!”— can't get there from here. And we got to Columbia, and Kramer's gonna go rehearse with them, and I'm there, and I had the opportunity to photograph all these people. There was Steve Beresford, who had, you know, done that Flying Lizard stuff. I go up to Steve Beresford, and I said, “You worked with Eno!,” because I'm a big fan of Eno. And Beresford looks at me, and his face turned red and he got angry. And he said, “He doesn't pay anyone!” So, I think that was the first time my bubble got burst that my heroes didn't always get along, and it wasn't this perfect world. And there was my biggest hero, Eno, being dissed by one of my other heroes for not paying them. Oh boy, what I was going to find out about the music industry after that. Because it could be a struggle to get paid, right? So I got the photograph and that was the one personal interaction that really stands out.

(Rehearsal for John Zorn’s Archery at the Miller Theatre at Columbia University, 1978. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): Then, several months later, I'm back up at CMS, and now, by this time, I'm in Karl Berger's house. And we're all in some living room type of thing in Karl's house— all these guys. There's probably fifteen of those student musicians there, and somebody comes in and says, “I got it! I got it!” He had Zorn's first record. That 2000 Statues record [actually the second he appeared on following 1978’s School LP with Chadbourne]. And I can remember sitting there, and the record just got passed around from person to person. Everybody looked at the record, and I realized that, boy, this Zorn guy really has a lot of respect from my friends. And, a hundred years later, I'm in Zorn's apartment, and I tell him the story, and I can tell he was really moved. He said, “You were there for that, huh?” And I don't think he had ever heard a story of what it was like for his junior friends to see that record for the first time. And I could tell there was this quiet pride. And Zorn said, “I gotta give you some records.” And he gave me every single record that he had there. I went home with like 20 albums because I told that story to John.

(Cover to the 2000 Statues LP The English Channel, 1979.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): Then I went to photograph Cobra at a place on Mercer Street. That was another really early game piece. Maybe 1982 I guess that was? And by that time, Zorn started to be a little more aware that I was around these gigs all the time, taking these pictures. Then one day he said, “I got an idea Macioce,” and would I come to his apartment. And I came to his apartment and he had these books of Japanese pornography and he said, “Would you want to do pictures like these?” And I'm like, “Well, I don't know.” It was stuff with people getting tied up and all that sort of thing. I didn't know if I'd do that. And he said, “okay.” I think he would've brought me to Japan to photograph weird stuff. I probably should've said yes to that, but I was honest and said, “That's a little weird for me.” He showed me these books with pornography and he says, “How about this then: how about you rephotograph some of these pictures in these books? Pick whatever ones you want to photograph, but do it in your infrared style.” So I photographed what I thought were the most dynamic of those pictures and did a roll of infrared film of this stuff. And he said, “Good, I want prints of this one.” So I looked at the contact sheet, I made these really big prints because he wanted to do them for a record that he had planned. I didn't know what record. And then the Torture Garden record comes out and there's my name in really, really tiny type. I'm glad about that later, because the cover became very controversial and banned in Japan. So I had gotten to do that. That's one of those things that I'm really proud I did, but I don't get to tell many people about it because it wasn't really my pictures, it was me interpreting them. I guess that's what people do when they sample, right? But Zorn wanted infrared photography, and that subject matter, and if I wasn't going to go to Japan and take actual pictures of that stuff, he had me photograph the books. So, you know, I have mixed feelings about that, because that’s somebody else's pictures that I re-photographed, but the way that they wound up using it for the record cover was really quite beautiful. John was working with a Japanese woman— Tomoyo was her name— she did all the covers of that early stuff then.

(John Zorn at CBGB, 1989. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): Then right around that time, he had Naked City play Torture Garden at the Knitting Factory. So, before the gig, Yamatsuka Eye came to my studio with Yoshimi P-We. She came with him and I got to do these wonderful [pictures]— I didn't realize how important it was to take a picture of them together. And that led to the other Japanese. I got to do Keiji Haino after that, with his band as well. And then when Yamatsuka Eye came back to pick up pictures— weeks, months, a year later. I don't even know how long later. I had the opportunity to turn him on to Ween. I had the Ween bootleg tapes. And I said, “Have you ever heard this stuff?” And I put the Ween tapes on, and I said, “You like it?” He says, “Yeah!”— he spoke very little English. “Very good. Very good,” he says. And I said “You want the tape?” And he says, “Oh, you give this to me?” And I give him one of my Ween bootleg tapes. Which Ween was nice enough to make me a new copy of. You know, they're really obscure, rare bootleg stuff, which eventually became part of The Pod anyway. And then the next thing I knew, I find out months later that Ween and Eye had done some sort of record together [1991’s Z-Rock Hawaii collaboration]. And that's another one of those things where, you know, I didn't get to do pictures, but I put Ween together with Yamatsuka Eye. So that's another one of those badges of honor, right?

(Yoshimi Pi-We and Yamatsuka Eye from The Boredoms at The Cave, 1990. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

(The Boredoms/Ween collaboration for Z-Rock Hawaii’s “The Meadow” from 1996.)

AV: I was going to say, you maintained a deep connection to the downtown scene well into the 90s and helped capture some of the most adventurous performers from that era, including groups like Sex Mob and Medeski, Martin & Wood. And also did that iconic photo for the Project Logic super group with DJ Logic on the Brooklyn Bridge. I was wondering if you could give a little context to the incredible genre-hopping that was continuing during that time period at places like the Knitting Factory and other venues, and things like DJ culture that began to be more heavily integrated into jazz, rock, world music, and everything else. You've talked about Christian Marclay, who was dabbling in that, but then you have somebody like DJ Logic and working with people like Marc Ribot and the Medeski guys— there's just a lot happening during that time period. Could you talk a little bit about some of those groups and working with them around that time?

MACIOCE: By 1990, the Shimmy-Disc records had been out for a couple of years and I had taken a lot of pictures of obscure musicians. So when some of these bands were coming up, like Medeski, Martin & Wood, I had a little bit of a reputation as the guy who does the unusual pictures of bands that aren't necessarily famous, but we all— we all, meaning the musicians— know are cool. So, you know, you go to these gigs, and sometimes it'd just be the other musicians from the scene that were there to see Sonic Youth at CBGBs with a small audience. It never happened later, but you knew the crowd. I can remember going to a Butthole Surfers show and standing there with Thurston Moore. It was a very small scene, but the people that were in the scene knew what was going on. So I think by the time 1990 came around, I had what was, for me, a reputation. But, you know, my reputation was small amongst this coterie of alternative musicians, before alternative became the name of the whole scene. I’m guessing Medeski, Martin & Wood got to me because of the work I had been doing for Zorn. Then Medeski, Martin & Wood might have been the connection to the Project Logic stuff. That shot on the bridge— we were very consciously trying to do a modern day version of the “Great Day in Harlem” picture by Art Kane. We were trying to do it with all the— I think the term they were using was the “jam band” or “groove musicians.” So I got to do that really fun picture with those Living Colour guys and Ribot with his daughter in the baby carriage. I was just really lucky to be the guy that they chose to take that picture. That picture came around 1999, I'm gonna guess, because I had met Dave Bias who was doing all the artwork for the Knitting Factory. And I started to do all those jazz musicians at the Knitting Factory.

(Medeski, Martin & Wood promo photo for Shack-man, 1996. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): That's something that I guess I should mention— the Knitting Factory really was like an access for me at that time. The Knitting Factory was still on Houston Street at the time, and you'd sneak in through the back door. I don't think I ever paid to get into the Knitting Factory. So I shouldn't complain that they never paid me for all the pictures I did for them on their big Jazz Fest tour. Mike McGonigal had his Chemical Imbalance magazine at that time and he asked me if I would photograph some of the artists for his magazine. I think that's how I got to do Steve Lacy. I'm trying to figure out who got me into the Knitting Factory to shoot Steve Lacy's picture, because I found myself at the Knitting Factory one day for sound check for Steve Lacy playing a gig. Was he playing with William Parker? I might have had to go to photograph one of those jazzy guys. I don't know. But there I was alone with Steve Lacy. He had no entourage, no friend with him or anything. It was just Steve Lacy rehearsing in that one light bulb lit room of the Knitting Factory. And I was like, “I’m here to take your picture.” He was like, “Okay.” He's just practicing, and I'm taking his picture, and he didn't realize I was just gonna start shooting right away while he was just noodling around on the sax. So he stopped playing and he put his suit jacket on to make sure he looked a little more distinguished. Steve Lacy— like he had to put his suit jacket on. The better picture was with the jacket draped over the chair and him looking like a working musician, but there was nobody there with him, it was just Steve Lacy. So that's how even a guy like Steve Lacey was under-appreciated by everybody except those musicians who knew he was one of the all-time greats. So, I was getting out there. You know, I lived on 10th Street, so it was not far for me to go to these places. I can say that the DJ Logic, and then the Medeski, Martin & Wood part of my photographic life, and those other 90’s type bands I took pictures of then, was because I got a little bit of a reputation at that point. Nobody was hiring me to go to Los Angeles and take Bette Middler’s picture. But there was a little buzz about me amongst those musicians. I'm really appreciative that I got that.

(Steve Lacy at The Knitting Factory, 1988. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

AV: Well, again, you took so many iconic photos that documented that era that it really is incredible and part of an incredible legacy for yourself— and those bands and artists— that would not exist without someone like you being out there and being willing to take the low-paying gigs or just to show up for the gig. It's a really amazing thing. Could talk a little bit about what you've done since then with your photography, both within music and outside of music?

MACIOCE: Now I mainly teach. I'm in the giving back part of my life. I'm 65 years old. When I was 21 years old I was a rock and roll photographer. I was very lucky. It's the kind of job that you could do if you came from suburbia and you were a white boy. And now that I'm a long-haired old white guy, I’m conscious of the privilege that I came out of. I mean, who gets to be a rock and roll photographer? It's a very privileged lifestyle. And I'm conscious about it. Politics was never very far from what I did— from being a rock and roll rebel and rebelling against the orthodox normalcy of the time. Remember, I come back from the 70’s, and if you come from the 70’s, you're really part of the late-60’s as well. So that whole hippie sensibility is what I grew up into. So, by the time I'm 60, I look back and was like, “I was lucky to get to do that.” I really should have been a more conventional person that did something else, but I was allowed to do this. There weren't a lot of female punk rock photographers. There were a few. Notable few, and I have such respect for them being able to do that in what was a guy's world. So now, I have a darkroom that's in Harlem, a community darkroom. We're a non-profit. I keep my tradition alive. We do grant-based programs. So like, homeless kids, we put cameras in their hand— they've never had a camera in their hand. They spend a week with us, we go to them, and take pictures. I have female photographers. In my teaching career, I've had a lot of female students, and they're feminists. And when Trump became president, they had a reason to be angry and pictures to take. So I've surrounded myself with people from the part of the culture that did not have the same privileges as me. Not to say it's all altruistic. Because I get a lot of street cred now for being this person to pass it on, and a lot of my students are young people that love this music now, like, “I get to hear from somebody that was at St. Vitus when they came in and closed the place down.” You know, some of these students, they love me for my knowledge of photography, but also for who and what I took pictures of. So that's the primary thing that I do, is a lot of my creative efforts in this school. I still do pictures for musicians, but usually if I'm doing pictures, it's kind of divided between the young bands that find me through Instagram and they were fans of the old bands that I took pictures of. Now there's these 23-year old kids that are in their own band and they're starting their journey. I did two bands last year from Pennsylvania— Laurel Canyon and Catatonic Suns. I got to find out that that area of Pennsylvania near Allentown has a real music scene. It's a cool music scene, too. So, they find me, and I get to be the crazy old photographer with these young guys and still do a photo shoot like I would have done, you know? I brought one of the bands to the Unisphere, just like I had brought the Tinklers to. I go and revisit locations that I shot at 30 years ago and bring young bands there.

(Catatonic Suns, 2022. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

MACIOCE (cont’d): I did a portrait of Dogbowl just before the pandemic. Or just after the pandemic started. I have one batch of the film that I used to use. I used to use black and white infrared film made by Kodak and they stopped making it in 2009. So I got Zorn to grant me some money to buy what we call a brick of film. Came from Alabama too, by the way. So I got twenty rolls for like $600. I got John to pay for it, and I have probably fifteen of those rolls left and I'll use a roll to photograph musicians that I photographed back in the day. Old photographers, when they get old, they go back and they re-photograph things they photographed when they were young. So, I like to do some portraits of the people that I've already taken pictures of. A couple weeks ago at the Whitney Museum, I photographed a fellow named Coby Batty, who now is the drummer for the reunited Fugs, but was in a lot of those bands with Kramer and Zorn. I photographed a couple of those guys with the Harry Smith show at the Whitney. The last day of the exhibit, we go up there and I photographed Steve Taylor and Coby with one of Harry's films playing in the background. So I do a little bit of that. And people find me. Instagram kept me alive. All those people that were part of my cohort in the 80s, they might not live in the Lower East Side anymore, but they do have Instagrams. And I'm in touch with them. It wasn't a very big scene when it was in New York, and it was the same 25 people at every gig you went to. But now, that scene spread across the globe where people can talk about it through Instagram, is big. I'm not a social media person. But I was starting to develop a blog page for my website just to put down the stories about what it was like when I photographed these people. And I had written about four stories. I wrote the Steve Lacy story, the Albert Jones story, and I realized, is this what people do Instagram for? So I opened an Instagram account. You won't find pictures of, you know, my breakfast or anything like that. It's really like my website was. It was an online portfolio where I get to tell my story and hopefully people write it in and can develop a conversation. Steven Bernstein of Sex Mob, he's one of my greatest “jazz sleuths.” I'll send him a picture, “Do you know who this is?” I have this picture of this saxophone player. I have no idea who it is. He writes back and says, “That's Knoel Scott. He's from the Arkestra.” And I find out who it is right away. And I'm like, “Who's this guy with a trombone playing in Carla Bley’s band from 1978? It's definitely not Roswell Rudd. Who the hell is he?” And Steve will say, “Let me call Karen and see.” That’s Carla's daughter. Call up Carla's daughter: “I’ll show it to my mom.” And then Carla's daughter shows her the picture of Carla Bley and Carla's like, “Oh, that's Gary Valenti. He's from Italy. He's normally a bass player, but he was on trombone that night.”

(Carla Bley Band, 1978. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

AV: Well, I was going to ask you, how important has Instagram been for you and your work in the modern era and getting it out there? I know for me, I've really loved connecting with your work through it and have seen a lot of other people do that as well.

MACIOCE: It has preserved what might not have been a legacy. Years ago, I was kvetching to Michael Azerrad about how difficult it was to be relevant even when you were relevant at one point. And he was like, “Just keep tending your legacy,” and that was the first time somebody had used the term legacy for what my body of work is. Instagram has given me a legacy, and it is at the same time that I get this validation that I made the right choices in my career path, it's also out there for all of those people that are into the music. When David Jackson, the saxophone player for Van de Graaf Generator lets me know that those were the best pictures of the band anyone ever took, that's part of my legacy. You know, it's not like I was taking pictures of Martin Luther King, where everybody in the world is going to know who it was. I was taking pictures of people that people are finding out about for the first time today. I published a photograph of Cornel Dupree, a session guitar player. He was playing with a band called Stuff at that time. And so I look up Cornel Dupree, and he played on all the Aretha Franklin hits, “Rescue Me,” and that sort of stuff. And I posted that picture. So what am I going to write about it? I said, “This is Cornell Dupree. He played on ‘Rescue Me.’” And people would write in, “I never heard of this person before. Thank you so much for tipping me to know who this is.” And I did a good deed for that person. I did a good deed for the Dupree family. And I did a good deed for me. So that's what it's done. I get to show off a little bit of my work, the stories, and maybe there's some young person out there that is putting two and two together about the music. Not necessarily about me, but about the music. And I feel, just like with my darkroom, that I am providing a service to my community. I provide a service to my New York City community by being a low-paid teacher willing to give up his secrets to a generation. And I give service to the larger community of the fans of that music that are spread out around the world and around different decades, but have that love for that music in common. So Instagram rescued me from old age with my photographs molding in the basement.

AV: Well, I can tell you it is an incredible legacy and an incredible service and I'm a huge fan of it. And have always been a fan of your work just having seen it throughout the years, whether it be in records for Shimmy-Disc or promotional photos, but to see it all collected together there has been really amazing and I hope more people are turned on to it. You can know that you have helped preserve a lot of amazing history.

MACIOCE: Thank you, Lee.

(Curlew at The Cave, 1991. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

(La Monte Young, Theatre of Eternal Music Big Band at The Dream House, 1991. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

(James “Blood” Ulmer, 1991. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

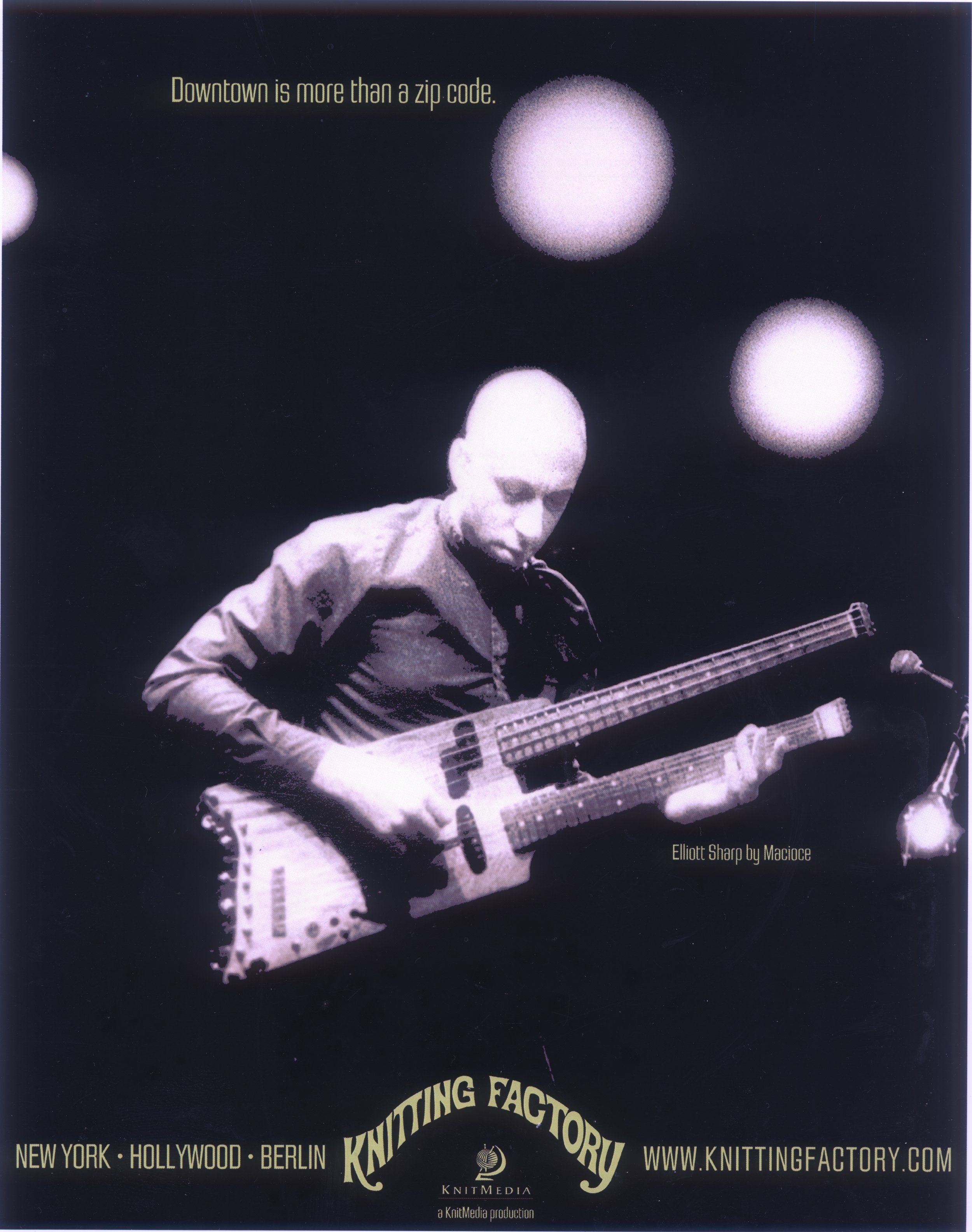

(Elliott Sharp, 1989. Photo by Michael Macioce.)

(Thurston Moore, 2005. Photo by Michael Macioce.)