Silver Apples Of The Moon

SILVER APPLES OF THE MOON

by Lee Shook

(Advertisement for Silver Apples’ self-titled debut album on KAPP Records from 1968.)

PHASE 1: MUSICA UNIVERSALIS

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

- excerpt from “The Song of Wandering Aengus” by William Butler Yeats, 1899

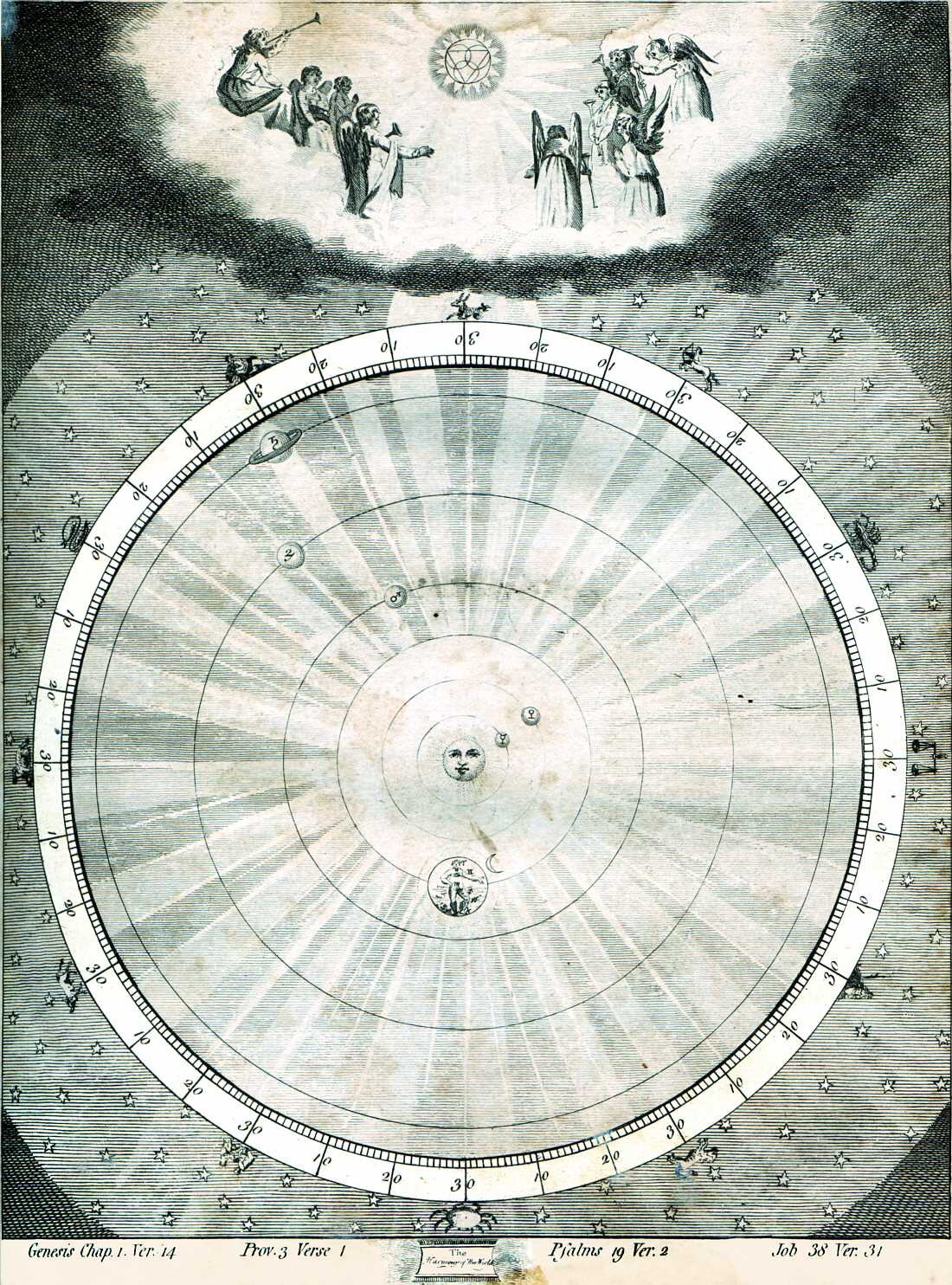

(Celestial Music of the Spheres.)

One has to wonder what William Butler Yeats would have thought about the symbolism and overwhelming sensory experience. Born in Ireland in 1865 and gone over 30 years, the Nobel Prize-winning poet would have no doubt marveled at the spectacle of it all: the magnitude of the moment; the modern media show and otherworldly images being beamed back from outer space; the free spirits cheering and dancing next to everyday citizens at what they were witnessing together; and, of course, the futuristic sounds emanating from the two musicians— Simeon Coxe and Danny Taylor, whose band name, Silver Apples, was inspired by one of his most famous poems— placed center stage as mankind took one giant leap onto alien soil and a foreign celestial body for the very first time in human history. As a man deeply indebted to cosmological mysticism and the metaphysical ideas and practices of his day, it surely would have blown his mind. But then again, it blew everybody’s— especially the musicians’— even through the contemporary historical lens of the Space Race era.

The date? Sunday, July 20, 1969. Better known as the day man first stepped foot on the moon. The place? The iconically pastoral section of Central Park known as Sheep Meadow— now rechristened “Moon Meadow” in honor of the evening— in New York City. The planet? Earth. The music? Cosmically symbiotic.

Had he actually been there to take it all in, Yeats undoubtedly would have taken some pride in having realized his 70-year old screed, “The Song of Wandering Aengus,” built on Irish folklore but now representing a modern global audience and countercultural zeitgeist through its musical namesake, was providing a direct connection between heaven and earth as the nation and world watched on in communal awe, regardless of race, class, creed or political ideology. Especially during the cultural and social upheaval felt around the country and globe that year. And being a part of the focal point of the evening wasn’t lost on the Silver Apples either.

(Picture of Nobel Prize-winning poet William Butler Yeats from Feb. 7, 1933 by Pirie MacDonald. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

“Looking back, I realize that it was the first and perhaps only time that all the diverse groups of our culture, from establishment to protest, were proud of our country at the same time and for the same reason. That made it a unique event in history,” says 81-year-old Coxe from his longtime home in Fairhope, AL. “I was very excited about the moon landing. The build-up to it had taken many years and it was talked about everywhere you went. Anticipation on that night was almost breathtaking. There was always the possibility something would go horribly wrong, and that only added to the intensity and the excitement. The whole world just came to a stop to witness that singular moment in time.”

As one half of the city’s most cutting edge electronic rock duo, and a man whose very instruments seemed to harness the spirit and sound of interplanetary transmissions from a distant galaxy, Coxe was already familiar with the connections people seemed to naturally make between the sonic sine waves being broadcast through his homemade board of oscillators, telegraph keys, and other electronic ephemera— appropriately nicknamed The Simeon by his record company— and the much vaunted “music of the spheres.”

“At the time our music was being described by some as ‘outer space music’ or ‘space rock’,” he says today looking back on the celestial alignment, “And we were saying, ‘No, no, no! Electronic music’s very ‘down to earth’- it’s just different from what you are used to hearing.’” Humorously adding, “I’m sure that our participation in this event reinforced their side of the debate.”

Having been dubbed “The New York Sound” by the city itself through Mayor John Lindsay for their innovative marriage of modern technology and trance-inducing rhythmic interplay, the Silver Apples were perhaps the perfect band to play the moon landing as part of the festivities surrounding the event in the most iconic modern metropolis on the planet, particularly as man took those first few apprehensive strides across the lunar plane as part of the Apollo 11 mission. As a regular fixture and house band at Max’s Kansas City, associates of Andy Warhol and The Factory scene, and a band that could be seen performing alongside people like Allen Ginsberg and The Fugs at the Fillmore East, there were few acts as integrated into the fabric of the city’s musical and cultural underground as Coxe and Taylor. Having emerged out of the ashes of the psychedelic blues rock scene as part of the Overland Stage Electric Band, who regularly performed at iconic venues like Cafe Wha? in Greenwich Village, and were friends with the likes of a young Jimi Hendrix through his association with Taylor, who would sit in on pick-up gigs with the burgeoning guitarist during his pre-fame days as a local gigging musician, the Silver Apples began their career about as turned on and tuned in as you could possibly be in the late-1960s in New York City. Having released their second LP, Contact, in early 1969 on the small KAPP Records imprint— itself a follow-up to their groundbreaking eponymous debut in 1968 and final official album during their all too brief lifespan— the band stood at the vanguard of contemporary rock and roll despite little of their sound resembling that of any of their peers outside of synth-oriented groups like San Francisco’s Fifty Foot Hose and LA-based electronic music pioneers the United States of America.

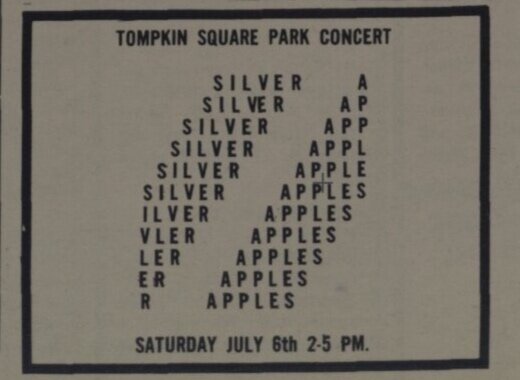

(Advertisement from The East Village Other for a free park concert with the Silver Apples from 1969.)

Combining Coxe’s oscillating drones with Taylor’s deep pocket grooves and expansive drum kit, the duo had caught both the eyes and ears of Lindsay the same year their debut came out as he sought to simultaneously tap into, and placate, the city’s countercultural movements during a period of civil unrest around the five boroughs. Finding the group emblematic of some of the more radical musical undercurrents humming around town at the time, Lindsay handpicked Coxe and Taylor to serve as de facto sonic ambassadors between city hall and the ever-growing hippie movement and radical left who were staging sit-ins, war protests and political rallies around the city, while also flipping the contemporary music and arts scene on its head. Having played several free shows in city parks to help bring people together in a peaceful atmosphere— including their very first live show in Central Park in front of 30,000 people in 1968— it was through Lindsay’s stewardship that they would find themselves front and center of the city’s cultural life during the heyday of not just the late-1960s, but one of the most momentous events in the history of mankind as it happened in real time in the heart of the Big Apple.

As Coxe recalls, “Mayor Lindsay started a program of periodic free concerts in several city parks and my manager knew somebody in the Cultural Department who was able to get us on the bill from the beginning. The mayor attended lots of these and developed a liking for our music to the extent that he once spontaneously referred to us as ‘The New York Sound’ during an introductory speech. The media picked up on it and it stuck. He specifically requested that we headline the moon landing concert and to try and time it so we would be playing when they were actually walking around the surface.”

(First page of the Silver Apples’ improvised score for “Mune Toon.” Courtesy of Simeon Coxe and Magic Theatre Music.)

Commissioned by the city to write a musical piece specifically for the occasion, and scheduled to coincide with the astronauts’ first forays on the lunar surface, after sketching out some general ideas on paper, Coxe would submit their rough score for the cheekily-titled “Mune Toon” to Lindsay’s team, providing a loose sonic framework for what would be the soundtrack to the dawning of a new era in space exploration, played alongside some of the band’s other original songs. Subtitling the proposal as “A Fairly-Organized Selection Of Musical Notes In Three Sections, By Silver Apples,” the song would feature three movements corresponding with Coxe’s mathematically-themed musical instructions and cosmic calculations, “to be first performed at the time that the first human being steps onto the moon’s surface.” Taking the audience on a journey through largely improvised compositional phases entitled “The Beginning— A New Era,” “Reflection And Elation,” and “Speculation Of Things To Come/Unanswered Questions/Confusion,” the suite was designed to be approximately just under 17 minutes long, which Coxe duly noted was the “quotient of the mean distance of the moon from the earth (238,857 miles) divided by the perimeter of the Simeon synthesizer in inches (235).” Subsequently getting the nod from the city to perform after reviewing their submission, the band would soon find themselves playing a pivotal role in Central Park during one of the most dramatic moments of the 20th century, and one that could have ended very poorly for both the performers as well as the mayor himself.

And although the Eagle would land safely in the Sea of Tranquility that fateful day, things were much less serene back here at home later that night. Especially in New York City, where the rainy weather became an increasingly unwieldy x-factor, causing both consternation and concern for all involved. Luckily for everyone who came to participate in the event, despite earth’s own atmosphere not cooperating with the proceedings, everything went roughly according to plan. At least for the most part.

(Simeon Coxe and Danny Taylor from Silver Apples in New York City, 1968. Photographer: Virginia Dwan.)

PHASE 2: RAINY DAY MOON-IN #12 & 35

Oceans full of bounty

That flows within their bodies.

Quiet but mighty rivers

Ride the fields of tomorrow.

- Silver Apples, “Water,” 1969

(Front page of The Village Voice covering the Moon-In from July 24, 1969.)

It goes without saying, but water and electronics generally don’t mix well together and can present a host of technical problems when presented side by side under the best of circumstances, especially in the concert setting. And for Simeon and his unruly board of jerry-rigged military surplus oscillators, technical gadgets and pedals, moisture was a constant concern when it came to performing live, where everything from environmental factors to spilt drinks could throw the finely-calibrated circuitry of his homemade contraption both out of whack and out of tune. It was a common occurrence for the band going back to their earliest performances, and Coxe had made a habit of being able to make improvised adjustments as needed during their live shows to be able to play their songs in accordance with key changes that could— and would— spontaneously arise at any given moment due to humidity and other unforeseen circumstances. Which made for an interesting scenario given the inclement weather hovering over the city the night leading up to Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong’s first moon walk and the throngs of cables, amps, cameras, giant TV screens, and industrial grade spotlights strewn across the Moon Meadow. Not to mention the handcrafted DIY frame and wiring of the Simeon and, of course, the electricity coursing through it all. Having faced a steady downpour of rain throughout the entire evening, it could have been a disaster in the making for both the Silver Apples as well as the overall success of the event— appropriately dubbed the “Moon-In” by the city in homage to the spirit of the era— and audience attendance in general.

As The New Yorker described the scene in a recent look back at the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission and its celebration in New York City at the time: “Hours earlier, as the rain came down steadily and a premature darkness fell over the city, hundreds of people streamed through Central Park and converged on the center of the Sheep Meadow to join the Moon-In crowd that was already standing in a huge circle around three nine-by-twelve-foot television screens set up in a triangular formation and tuned to three different channels. The Meadow was filled with puddles and mud holes, and many of the younger spectators had shucked their shoes and were negotiating the slippery terrain in bare feet. Some people carried umbrellas, others pulled coats or jackets over their heads, and a good many seemed happy simply to give themselves up to the rain and the prospect of a soaking. In front of the C.B.S. screen, five young men in beards shared a large green-red-and-yellow striped beach umbrella; next to them stood a couple huddled beneath a bed quilt; and nearby three girls who had contrived a makeshift tent out of an Army-surplus blanket and a pair of sanitation trash baskets were playing Scrabble. Overhead, three searchlight beams met, forming a soft halo of haze, through which the rain fell in silver sheets.”

(Picture of Moon Meadow in Central Park from July 20, 1969. Photo courtesy of NYC Parks Photo Archive.)

Wet, muddy and with the potential for serious electrical hazards— not unlike another iconic countercultural event that would take place in upstate New York just a few weeks later— it was not the optimal environment for a band like the Silver Apples to perform in, or, for that matter, the crowd gathered to see both them and man’s first steps on the moon. Yet despite the challenges for everyone involved, both the people and event pressed forward through the intermittent showers, waiting patiently through the rain to witness the historic affair and even sneaking in a little free love along the way.

As Coxe humorously remembers, “It rained off and on during the whole evening but people didn’t seem to care. As a matter of fact, I noticed a lot of people were taking shelter under tarps, or even just crawling under bushes and making babies. I wonder if there was a spike in the city’s birth rate 9 months later.”

With thousands gathering on the muddy field as the scheduled time for the hatch opening and moon walk approached and the world’s first glimpse of American astronauts as they made their way out of the lunar module, despite the Moon Meadow’s strong hippie contingent and vibe, the audience turned out to be a classic melting pot of New York City’s larger population, with people from all over joining in the communal scene and worldwide news coverage.

“The crowd was a cross section of the entire city— old and young, Wall Streeters, media stars, cops, construction workers and hippies all mingled together in one happy undulating mass of people— all walks of life,” remembers Coxe. “Dozens of roving news crews interviewed everybody in sight and massive searchlights swept the sky. A real media frenzy. Silver Apples was not really a part of the coverage because we were scheduled to play toward the end of the evening and all the news crews and filmmakers had completed their ‘crowd coverage and interviews’ by then and when we finally came on to play they were nowhere to be seen, concentrating on just the actual moon walks.”

(NYC Moon-In melting pot. Photo courtesy of NYC Parks Photo Archive.)

Having officially landed on the moon earlier that afternoon at 4:17 Eastern Daylight Time, it wasn’t until approximately 10:39 pm that night that both the nation and world got word that Armstrong was ready to open the hatch and make his appearance descending the ladder of the Eagle as the lunar module had finally settled in and the appropriate system checks were made and spacesuits were donned to ensure a safe moon walk. Yet despite the overwhelming anticipation— for both the crowd and the Silver Apples— the wait wasn’t quite over.

Again from The New Yorker: “As the scheduled moment for the hatch opening approached, the crowd grew still and every gaze appeared to be fixed on a television screen. Then came an announcement that the moon walk would be delayed for half an hour, and there was a sustained groan of disappointment. At a quarter to ten, Houston could be heard through a crackle of static calling to the command module, and a few minutes later the crowd, which had grown hushed again, burst into applause when the astronauts were informed by the voice of Mission Control, ‘You are go for cabin depressurization.’ The rain stopped and started several times during the next half hour, and dozens of spectators, weary from standing and long since soaked, began to sit down in the wet grass and mud. When the hatch opened, and Armstrong’s booted foot could be seen groping for the rungs of the landing vehicle’s ladder, and the totally unreal words ‘live from the surface of the moon’ appeared upon the screens, there was a gasp, as if everyone had taken a quick breath. There was a smattering of applause, and then dozens of flashbulbs began popping as cameramen took pictures of a vast sea of faces held perfectly still at the same upturned angle and frozen into identical expressions of rapture and awe.”

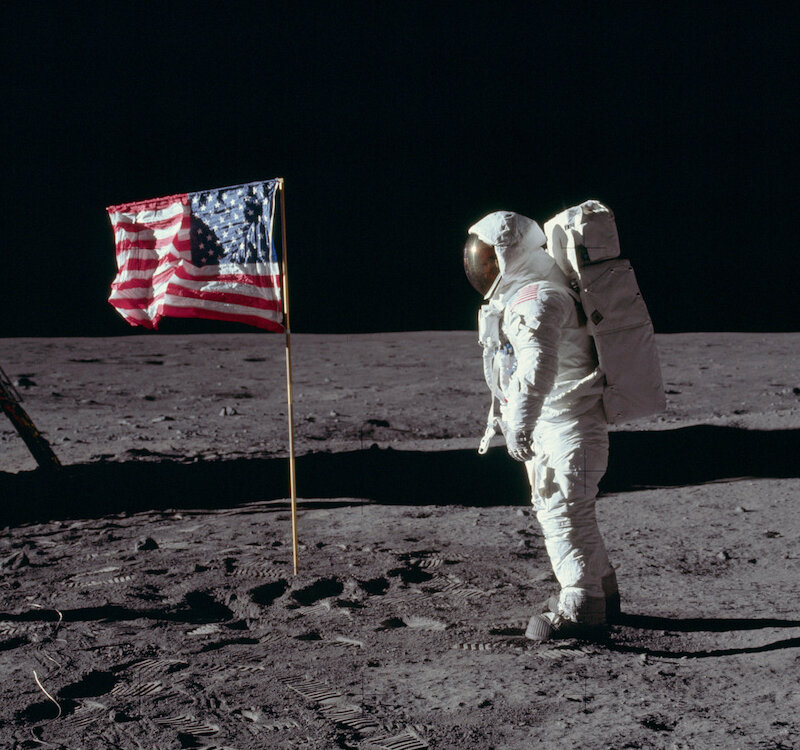

A moment broadcast live to an estimated half a billion people around the planet, for those watching on the giant screens in the Moon Meadow it was also a momentous occasion well worth the minor hold-ups despite the uncomfortably soggy conditions. And for the Silver Apples, it was also a moment that would delay their performance of “Mune Toon” for nearly another hour. Watching on with the rest of the world as Armstrong relayed by radio his famous line, "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” as he first placed his left foot on the moon’s dusty, grey surface, the group would have to wait through Aldrin’s exit from the capsule, as well as several adjustments of the crew’s live camera for the audience at home, the planting of the American flag, and an address from both President Nixon and Mayor Lindsay, before they could finally take the stage and fire up their oscillators and drums. But they weren’t the only musical entertainment for the night. Having been preceded by a local big band ensemble just prior to their performance playing jazz standards like “Blue Moon” as the 10,000-strong crowd stared and listened in rapt attention at the images and words being broadcast back to them on the big screens, as the midnight hour approached the scene in Central Park couldn’t have been crazier— or more electric.

“As I recall, the other band was to play when the first contact was made with the surface, then they were to clear stage for us to be ready to play when they actually started walking around,” says Coxe, “We did this in a hurry, not knowing when they would emerge. When Mayor Lindsay came on to announce that the walking around was imminent, it had just showered and there was a puddle in the front of the stage. When he grabbed a microphone to make the announcement, I swear his ears lit up! He was receiving a large electrical shock and couldn’t let go of the microphone. The plug for the sound system was within reach so I quickly yanked it out of the wall. His security got him to dry ground and he was able to continue— but I am haunted by the memory of the inadequately grounded Silver Apples sound system nearly electrocuting the Mayor of New York.”

(Mayor John Lindsay being interviewed either pre or post-shock at the Moon-In in Central Park in 1969. Photo courtesy of NYC Parks Photo Archive.)

Launching into their set as the astronauts bounced and glided over the moon’s surface in zero gravity, scooping up rock and soil samples, conducting experiments, and describing what they were seeing to the world, Coxe and Taylor let their unearthly sound serve as the sonic backdrop against which the cosmic human drama unfolded in real time. Playing “Mune Toon,” alongside the rest of their live repertoire from their two albums, it was a tense but exciting moment that would serve as one of the high points of their all-too-short career as one of the leading lights of New York City’s progressive rock and roll underbelly.

As Coxe once recounted to UK website Ptolemaic Terrascope in 1996, “I was receiving electrical shocks every time I touched the instrument but there was nothing that seemed like it was life-threatening so we kept going. I knew that to touch the microphone was zap city…..but there was definitely a connection being made between the bass platform and the top oscillators. I just kept my hands on the oscillators because I found that when I let go and then tried to re-touch them, that was when I got zapped. So all during 'Mune Toon' there was this tingling, sexy, frightening, scary thing coursing through my body and I was singing my heart out and Armstrong was stepping onto the moon and human beings were entering a new era and thousands of people were crying with happiness and soaking wet and singing and hugging each other.”

(Simeon Coxe playing the Simeon. Photographer: Barry Bryant. Courtesy of Magic Theatre Music.)

Yet as “charged” as the astral occasion was as a milestone in human history, as Coxe recalls, it also had the distinct flair of a supremely psychedelic celebration for many of the attendees in the audience. “I just broadly remember the realization that humankind had, at that moment, entered a new age in its development— probably as profound a moment as crossing over from the Stone Age. We were, naturally, well aware of the importance of the event and felt honored to be a part of it,” he says today looking back on it all. “Surprisingly lots of people who were congregated in front of the stage were doing their twirl-around hippie dancing and not paying much attention to what was happening on the moon. They were probably on their own much more interesting planets anyway. We played everything we knew and then repeated some. Their walking around and gathering rocks took forever and we just kept playing while the astronauts did their thing.”

As The Village Voice’s Steve Lerner reported in his article from the time, “The Age of Lunacy On a Muddy Meadow,” the event was akin to the “world’s largest outdoor multi-media program” and the “groovy intergalactic vibes from the Silver Apples” were only one element of the grandiose spectacle. “Circus tents had been erected to serve the hungry multitudes lunar hotdogs, satellite donuts, and Cosmic Cokes. Pan Am had a booth where you could sign for their first trip to the moon. And standing near to a clump of ultra-violet trees, a group of students from the School of Visual Arts, dressed like lunar versions of the Ku Klux Klan, were holding onto the fringes of a parachute and throwing a colored beachball up in the air like an Eskimo child on a blanket. For some obscure reason they called their activity a Moon Dance,” he recalled from the evening. Wryly adding that, “those in Central Park fell back on the ‘In’ form of rejoicing — of be-in, love-in, and smoke-in fame — in order to be as up-to-date as possible in the new Age of Lunacy. Of course from the moon it all must have looked fairly foolish.”

(Students from the School for Visual Arts dance in front of the stage while the Silver Apples perform during the moon walk, with The Simeon oscillator board and Simeon Coxe featured back right. Photo courtesy of NYC Parks Photo Archive.)

Yet despite the technicolor tomfoolery, it was still an amazing communal event of epic proportions, and one that not only the Silver Apples capitalized on in New York City, but would also play out thousands of miles away across the Atlantic as English psychedelic rockers Pink Floyd performed their improvised tune “Moonhead” live on the BBC as part of an Apollo 11 special for the Omnibus program called “So What If It’s Just Green Cheese?”— four years before their landmark album The Dark Side of the Moon— as Armstrong and Aldrin took some of their first interplanetary strides on the luminous orb. Followed on the same broadcast by a newly-minted single entitled “Space Oddity” by a still relatively unknown young singer named David Bowie— who had written the track in hopes of capitalizing on the lunar madness sweeping the globe at the time— despite the Brits’ homage to the event, as born and bred Americans on native soil, it would be the Silver Apples who perhaps most proudly and effectively carried the day— rain be damned— offering up a distinctly futuristic sound for the new space age from the Greatest City on Earth as our nation first made contact with the moon for all of humanity.

Sadly, it would also serve as one of the Silver Apples’ last big hurrahs in the town that helped make them famous.

(Moon walk photo from the Apollo 11 mission from 1969. Photo courtesy of NASA.)

PHASE 3: COSMIC WIND/CELESTIAL SAILOR

Sail over distant waters

Til you reach the honied shore

Walk on through purple flowers

Breathe the golden fragrance

You have reached the final island

Where dreams light up the daytime

You are at the end of journey all is peace.

- Silver Apples, “Velvet Cave,” 1968

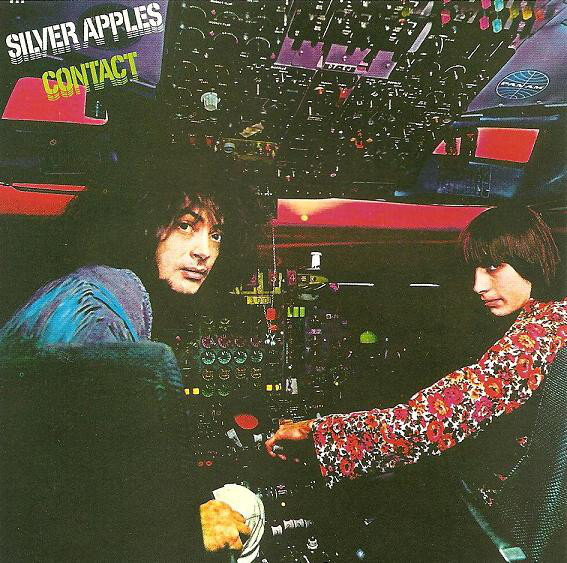

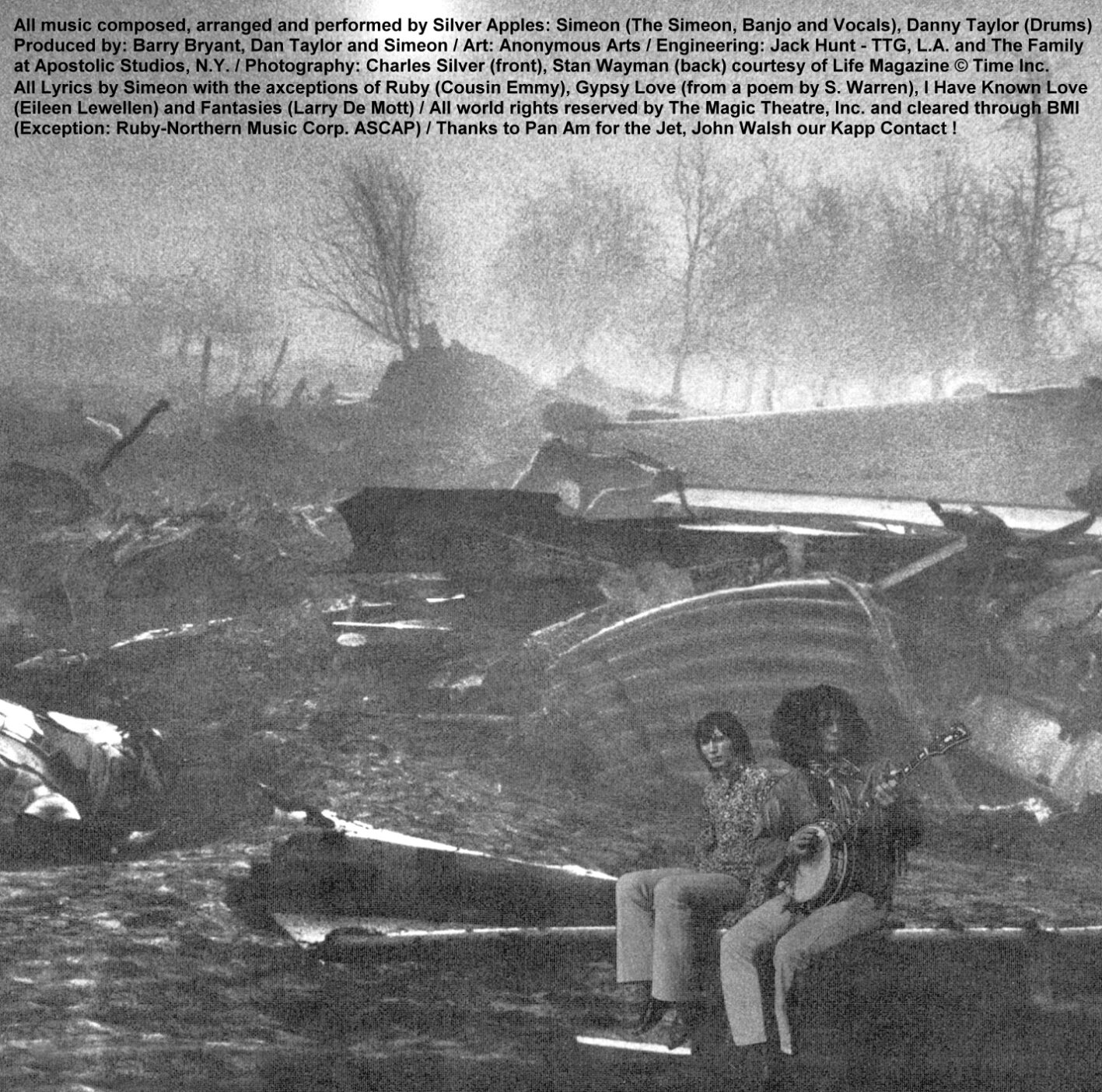

As astrological fate would have it, although it was a night to remember on the muddy meadow, and one that only they could claim in the history of American rock and roll, things would quickly turn south— both literally and figuratively— for Silver Apples as the band’s promising career would soon be snuffed out at the height of their prestige and powers following their performance in Central Park. Running into legal trouble with Pan Am airlines over the band’s cover art for Contact earlier in the year, which would feature Coxe and Taylor on the front cover sitting in one of their airplane cockpits looking both serious and possibly stoned, with drug paraphernalia surreptitiously hidden in frame as a blazing hot orange sun set in the background and the duo ostensibly readied for “takeoff,” the back cover would prove even more problematic for the company brass, prompting a massive $100,000 lawsuit. Featuring a darkly humorous depiction of the hazy wreckage of a downed Swedish airliner with the Apples superimposed eerily on top— with Coxe coyly plucking away at a banjo on his knee— although the band had initially gotten approval from the company’s lawyers through KAPP’s ad agency to print it, after some higher ups seeing the band’s usage of their name and intellectual property in such a potentially negative light after the records had already hit the shelves, Pan Am would sue not only the Silver Apples out of existence, but their entire record label as well, bringing an unceremonious end to both the band and KAPP. Pulling all of the unsold albums out of record stores around the country and ending promotion of the LP, it was a move that would effectively kill the duo as a functioning and marketable group. The company also went after Coxe and Taylor personally, abruptly confiscating Taylor’s drum kit after a performance at Max’s Kansas City, with the Simeon barely eluding repossession after having been hustled offstage beforehand when they realized what was going on. It was an unfortunate demise for both entities, and one that saw a third Silver Apples album recorded towards the end of 1969 at The Record Plant in New York City as they searched for a new label, titled The Garden, remain unreleased until 1998 following renewed interest in the band after decades of obscurity as a footnote in the history of revolutionary rock and roll from the generation that brought the world Flower Power.

(Front cover to the lost Silver Apples album The Garden from 1969.)

It was also an event that would send Coxe, who had been born in Knoxville, TN and raised in New Orleans— and was a tried and true Southerner at heart— back below the Mason-Dixon Line to start a new life away from the hustle and bustle of the Big Apple. Having amicably split ways with Taylor following the lawsuit and briefly trying out a new version of the Silver Apples as a three piece for one gig in early 1970 opening for guitarist Larry Coryell at The Village Gate, as well as working as a club DJ, Coxe soon realized his time in New York had finally run its course. Jumping on a small sail boat he had recently purchased in October of 1970, and sailing from New York harbor with his girlfriend Eileen, down the Eastern seaboard along the intracoastal waterway, and away from the harsh Atlantic ocean and winter storms, he would eventually arrive in Mobile, Alabama, where his parents and brother lived, just before Christmas that year nearly three months later. A long, but largely uneventful journey, aside from days spent out on the water, seeing wild parrots, and watching a rocket launch (appropriately enough) at Cape Canaveral along the way, it was a voyage that also left plenty of time to reflect on all that he was leaving behind in the big city as he prepared for a new beginning in his maternal homeland in the Heart of Dixie. Having shipped The Simeon by land to Alabama, his namesake instrument would go permanently dormant following his arrival, marking the end of a decade-long pilgrimage that had initially started with ambitions of being a visual artist alongside the likes of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, but had taken an unlikely turn into the realm of innovative, sci-fi infused rock music.

Settling into a far more laid back cadence and lifestyle compared to his wild and wooly days in New York City performing in front of members of The Velvet Underground, and separated from his longtime partner in crime, with Taylor plotting his own hushed course away from the band, it was a massive change in scenery that would find him temporarily rudderless while figuring out his next steps in his new home town. Initially reintroducing himself to the regular world by taking up a job as an ice cream truck man, he would soon stumble into an accidental career as an editor, cameraman and eventually on-air news reporter for local television station WKRG, marking yet another unlikely chapter in an already exceptional life story. Discovering a knack for television, it was a surprising transition that would eventually see him move between Virginia, Maryland and eventually back home to Mobile over the course of the next few decades as an award-winning newsman, before turning his attention back to his first love as a visual artist. Reconnecting with his roots in painting dating back to his pre-Silver Apples days as a young man in New Orleans, and the reason he initially moved to New York in the first place in the 1960s, needless to say, it’s been a strange trajectory for a man who once jammed on the “Star-Spangled Banner” with Jimi Hendrix, opened for the MC5 and Blue Cheer, hung out with the Grateful Dead, and played the moon landing.

(Front cover to the 2016 feature piece on Silver Apples from The Wire.)

Adjusting to a much quieter existence during his stints on the East Coast, it wasn’t until finding out about a renewed interest in the music and legacy of Silver Apples in the 1990s— kickstarted by the release of illegal bootlegs in Germany of the band’s first two albums on the TRC label, followed by copious sampling from everyone from house music DJs, to indie rockers like The Folk Implosion, and Brit-pop stars like Blur— that Coxe would revisit his past in any meaningful way. Triggering a new era in Silver Apples activity that would find him not just performing and recording again, but also serendipitously reconnecting with Taylor in the late-90s, who would discover the original reel-to-reel tapes of their last unreleased album in his attic, allowing for the world to finally hear one of the great lost treasures from their catalog after being released on the Whirlybird Records label in 1998. And although he would never perform again with Taylor, who would unfortunately pass on March 10, 2005 from a heart attack after a long battle with a degenerative muscular disease, Coxe has managed to keep the Silver Apples’ interstellar sounds and legacy alive, continuing to put out highly original records with a host of younger musicians and working with producers like Steve Albini, touring around the world under the band’s fortuitously ethereal moniker through today, making him one of the last great 60s underground rock icons to still be pushing his— and their— music forward into the future. Having lost most of the original Simeon board to a flood caused by Hurricane Frederic in 1979, where it was swept out of his brother’s basement and into the silty bottom of Mobile Bay never to be seen again, Coxe’s ever-pioneering artistic spirit has allowed him to effortlessly adapt to modern technology, making use of hybrid rigs that presently incorporates both traditional oscillators as well as computer-based samples, including some of Taylor’s original drum parts from the three LPs, triggered through an Akai S20 and programs like Ableton Live. Considered an inspirational influence by everyone from Spiritualized and Stereolab to Deerhoof and Portishead, it’s an incredible story that’s still playing out well into the 21st century, even going so far as to revisit the legendary “Mune Toon” in 2008 as part of a collaboration with artists Amir Mogharabi, Stefan Tcherepnin and Jeffrey Perkins at the Kitchen in New York City, as well as part of a special performance with early psychedelic projection pioneers The Joshua Light Show— updated and digitized for the modern era, much like Simeon himself— to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Apollo mission in Houston, TX in 2009.

And that may just be the greatest cosmic journey of all, and one whose poesy Yeats would wholeheartedly approve of.

(Front cover to the 2019 Record Store Day release for Oscillations 2019.)